Chapter 5. Investing for social impact in developing countries

Social impact investors seek social and environmental impact from their investments, in addition to financial returns. This chapter discusses the potential of social impact investment for developing countries, highlighting several examples to demonstrate how it works in practice. It examines the challenges, including assessing whether interventions have achieved their intended impact and expanding the evidence base. The public sector can promote social impact investment, for example by providing risk capital to enable the private sector to offer affordable, accessible, quality products and services to the poorest populations. The chapter makes recommendations for increasing the reach and the scale of social impact investment.

Challenge piece by Julie Sunderland, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Opinion pieces by Manuel Sager, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; Sonal Shah, Beeck Center for Social Impact & Innovation, Georgetown University.

Julie Sunderland, Director of Program-Related Investments, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

It’s not surprising that the private sector faces challenges in serving bottom-of-the-pyramid customers: the largest and poorest population groups. By definition, bottom-of-the-pyramid populations don’t have much income, making margins slim. In addition, the often weak infrastructure and distribution channels in developing countries make the transaction costs of reaching these customers high. Much of the procurement of basic goods and services for the poorest populations goes through government-managed development co-operation channels, which are often bureaucratic and opaque to companies.

Nonetheless, there is still great potential for the private sector to serve bottom-of-the-pyramid populations. Capital flows into the private sector, both via investment and revenue, dwarf flows from philanthropy and development co-operation combined. The private sector’s commercialisation and manufacturing capabilities can allow for scaled production and delivery of affordable, life-saving products. The private sector can bring critical knowledge, capabilities and resources to solving social sector problems, and its capacity for research, development, innovation and entrepreneurship can be applied to generate transformative technologies and new business models.

Social impact investment can help to realise this potential. When done well, it can address market failures that keep the private sector from investing in social sectors. At the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we’ve seen in practice how patient, flexible risk capital can support innovative models that provide affordable, accessible, quality products and services to bottom-of-the-pyramid populations. When done badly, however, social impact investment can distort markets and prop up unsustainable businesses.

For social impact investment to become a credible bridge to a private sector focus on bottom-of-the-pyramid populations, it needs to address three challenges.

Align incentives for social and financial goals. Except for the limited resources allocated to corporate social responsibility, private companies and investors are driven by financial goals. While a new class of impact investors may be willing to sacrifice some financial returns to generate social impact, investment capital at the very least needs to be repaid out of the cash flows generated by the business activity. One of the current challenges for making social impact investment work effectively, therefore, is identifying (and working creatively to expand) the opportunities for aligning revenue/profit generation with the achievement of social goals.

A great historical example of such alignment is the proliferation of cellular technology. Mobile phones have had significant social impact in fields as diverse as disease response, financial inclusion and technical assistance. Mobile phone companies have also provided excellent returns for their investors. Yet most social goals will lack the natural alignment with scale and profit evidenced by mobile telecommunications. Social impact investment has the potential to bridge this gap through risk reduction mechanisms, such as guarantees; through the application of low-cost scaling capital to validate nascent distribution models; and through company-building equity investment in technologies that hold promise similar to that of mobile phone technology.

Change the economics of reaching bottom-of-the-pyramid populations. Capital-intensive, complicated or transaction-heavy business models that might work elsewhere will not be sustainable in bottom-of-the-pyramid markets. The private sector can develop new technologies, products and business models that are adapted to the needs of bottom-of-the-pyramid populations, allowing for rapid uptake and producing high sales volumes, even if margins remain slim. For example, there are innovations that have the potential to cut delivery costs, ranging from sachet-sized consumer products to agent-based distribution models and pay-as-you-go financing. Social impact investment can support the further development and demonstration of these new business models by leveraging and, ultimately, crowding in private sector investment.

Cultivate top-tier, on-the-ground investment and entrepreneurial talent. Access to capital is often cited as a primary limitation to the growth of small and medium enterprises, and to social sector businesses. Yet access to talent may be a bigger and more persistent constraint as promising models replicate and grow. Social impact investment needs to develop two levels of talent: strong intermediaries and fund managers who are good at allocating capital and building companies; and strong entrepreneurs and managers to lead social sector businesses.

Over time, improving secondary and post-secondary enrolment and education, and increasing entrepreneurial expertise in local markets and among diaspora, will allow talent to flourish. Social impact investors can speed up this process by taking the risks and investing in emerging intermediaries and entrepreneurs, recognising that while they are learning they will be developing experience and networks. A handful of successful cases can encourage others in the private sector to seek out and further develop untapped human capital.

Social impact investment is the use of public, philanthropic and private capital to support businesses that are designed to achieve positive, measurable social and/or environmental outcomes together with financial returns (OECD, 2015c). It has evolved over the past decade as a means of using traditional development financing, in particular official development assistance (ODA), to develop new business models that can complement existing ones.

Social impact investment can not only help to direct new capital flows to developing economies; it can also bring greater effectiveness, innovation, accountability and scale to investments, increasing their economic and social benefits for the world’s poor (SIITF, 2014a). For example, a study by the United Nations Development Programme shows how in Africa, capital flows from the private sector and philanthropic actors are offering opportunities for impact investors to increase access to basic services for healthcare, education, clean water and energy (UNDP, 2014; and see Box 5.1).

SDG 7 calls on the global community to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” (UN, 2015). The demand for energy is growing in developing countries, with estimates of the need for investment in renewable energy at around USD 34 billion (UN, 2015; Schmidt-Traub and Sachs, 2015).

Many companies are already rising to the challenge. For example, in Africa M-KOPA Solar is offering “pay-as-you-go” solar energy for customers who do not have access to more central resources. Since its commercial launch in October 2012, M-KOPA has connected more than 300 000 homes in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda to solar power, and is now adding over 500 new homes each day. It offers solar energy to low-income households at affordable prices using a pay-per-use system. Aside from being cheaper than traditional kerosene lighting, solar-powered energy is better for human health and for the environment. Based on a calculation of 1.3 tonnes of CO2 reduced per M-KOPA solar system over four years, the company estimates that it has helped to reduce 260 000 tonnes of C02.

M-KOPA draws on a team of Kenyan and international software engineers who have built the platform from the ground up. For example, embedded sensors in each solar system allow M-KOPA to monitor real-time performance and regulate usage, for which fees are collected via mobile phone systems. The innovative M-KOPA business model has enabled the company to take their solutions to scale, spreading success by creating jobs for 650 full-time employees and 1 000 commission-based sales agents.

For more information see: www.m-kopa.com.

Pay-as-you-go solar energy in Kenya has helped to reduce 260 000 tonnes of C02 over four years.

Examples like this illustrate how the power of markets combined with innovative ways of efficiently and effectively using public and private capital can be channelled to bring solutions to urgent social, environmental and economic challenges (see the “In my view” box by Manuel Sager). While these innovative approaches will not replace the core role of the public sector or the need for philanthropy, they can provide models for leveraging existing capital to produce greater social impact (Wilson, 2014).

Manuel Sager, Director-General of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

Partnerships between the public and the private sector can take on many forms. When it comes to leveraging additional resources for sustainable development, social impact investors are key partners for development agencies. They include private and institutional investors that seek not only financial returns, but also social and environmental improvements. The market for social impact investment has been growing steadily in recent years. It makes sense for development actors to pay greater attention to this investor segment and to look for synergies with it.

In Switzerland, for example, the volume of investments seeking social impact in developing countries is substantial: in 2015, assets under management for such investments in the country amounted to an estimated USD 9.85 billion.1 While the global impact investment industry is still in its infancy, it is set to grow significantly over the coming years. Investors are increasingly interested in returns other than purely financial ones and seek new investment classes to diversify their portfolios.

Given the close alignment between the goals of impact investors and those of the international development community, it seems only natural that the two sides should engage in more mutually supportive partnerships. This would strengthen the impact that socially oriented capital has on poor communities, particularly in lower income markets.

In my view, there are four key areas in which development agencies like the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation could do more to partner with the impact investment industry and support the transformation of social impact investment into a mainstream choice.

First, partner governments and development co-operation agencies should not neglect the important objective of strengthening the overall governance framework in developing countries. This is essential to create attractive investment opportunities, including for impact investment. After all, impact investment decisions are informed by the same factors that make a business environment attractive for other forms of investment. These include effective public administration, rule of law, a sound macroeconomic framework, low levels of corruption, and easy, transparent business procedures. Switzerland will continue to work with its partner countries to improve their overall business climate and promote good governance, including in the world’s least developed countries and in countries emerging from conflict.

Second, the public sector can support a number of activities to help reduce the cost of impact investment relative to other types of investment. Switzerland has created the Swiss Capacity Building Facility2 for this purpose. The facility is a public-private partnership that provides small technical assistance grants to financial service providers in developing countries. Its contribution reduces the entry costs for those seeking to offer innovative and affordable financial services to low-income earners, smallholder farmers and small businesses. Financial products such as agricultural input insurance or livestock leases allow clients to boost their income, employ more people and reduce their vulnerability.

Third, where it makes sense, public funds can be used to leverage private funds via guarantees or early-stage investment. One of the most successful microfinance funds in Switzerland – the responsAbility3 Global Microfinance Fund – was launched in November 2003 with initial capital of CHF 3.6 million from the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs. Today, this is a flagship microfinance fund worth over USD 1 billion in private capital invested in various microfinance institutions in developing and transition economies.4

Finally, development actors and the social impact investment sector need more platforms for exchanging knowledge and sharing experiences. This dialogue can help them identify what works and what doesn’t work, and to ensure that the right incentives are put in place on both sides to advance the goals of the 2030 Agenda. In Switzerland, the sustainable investment community, which comprises a number of impact investors, has banded together under the auspices of the Swiss Sustainable Finance5 organisation to help establish the country as a leading centre for sustainable finance. To date, Swiss Sustainable Finance comprises over 80 members from Swiss banking, insurance and financial services, and includes a working group on investment for development.

As we set out to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, it is clear that social impact investors can make a big contribution. What we need now are smarter policies to enlarge the circle of contributors.

← 1. Swiss Sustainable Finance (2016), “Swiss Investments for a Better World. The First Market Survey on Investments For Development”. The classification used in the survey entitled “investments for development” summarises investments that combine three necessary elements: the intention to improve the social, environmental and/or economic situation in the investment region; target low or middle-income frontier countries; and aim for returns in line with other investment categories.

← 2. http://scbf.ch.

← 3. www.responsability.com/investing/en/678/Investments-AG.htm.

← 4. www.responsability.com/investing/en/1061/responsAbility-Global-Microfinance-Fund.htm?Product=19665.

This chapter examines the concept of social impact investment in the context of other forms of private sector contributions to sustainable development. It discusses both the potential and the challenges of social impact investment in developing countries, providing illustrative examples of how it works in practice. It concludes by offering recommendations for fostering social impact investment in developed and developing countries.

Development challenges offer opportunities for social impact investment

Social impact investment tends to target sectors that have difficulty attracting other forms of private investment, such as renewable energy, rural development and health (Simon and Barmeier, 2010). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) address global challenges in many of these sectors, from food security (SDG 2) to health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4) and sustainable energy (SDG 7). Written into all of these goals is the need for more efficient and effective social service delivery (UN, 2015). Private investors and public development agencies can make solid contributions to financing the achievement of the globally agreed SDGs by aligning resources and knowledge to leverage the potential of social impact investment.

The delivery of social services is complex and entails a number of challenges. A growing number of non-state service delivery organisations – such as community organisations, charities or non-profit organisations, social enterprises, social businesses and social impact-driven businesses – are specialising in addressing social needs using innovative business models (Box 5.1). Social impact investment can play a critical role in preparing markets to support the growth and scaling up of these models to benefit the poor and disenfranchised (Koh, Karamchandani and Katz, 2012).

Enthusiasm for social impact investment is growing

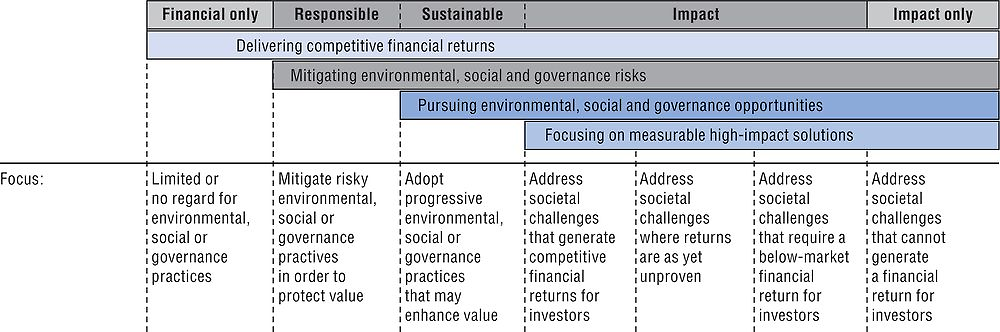

Capital can be invested along a broad spectrum: some investors are interested exclusively in financial returns, while others focus on the social and environmental impact of their investments (Figure 5.1). A growing number of private investors are interested in achieving both social and financial returns, with varying degrees of preference for one over the other.

A growing number of private investors are interested in achieving both social and financial returns.

Source: Adapted from Bridges Ventures (2015), “The Bridges spectrum of capital: How we define the sustainable and impact investment market”, Bridges Ventures, London, http://bridgesventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Spectrum-of-Capital-online-version.pdf.

Social impact investment offers a way of diversifying investment. It has the potential to catalyse new capital flows into developing economies while at the same time translating experience, policies and approaches from developed countries to emerging and less developed ones. Social impact investors in developing countries include foundations, high net-worth individuals, early-stage venture funds, private equity funds, development finance institutions and other institutional investors (Table 5.1).

Foundations have pioneered social impact investment

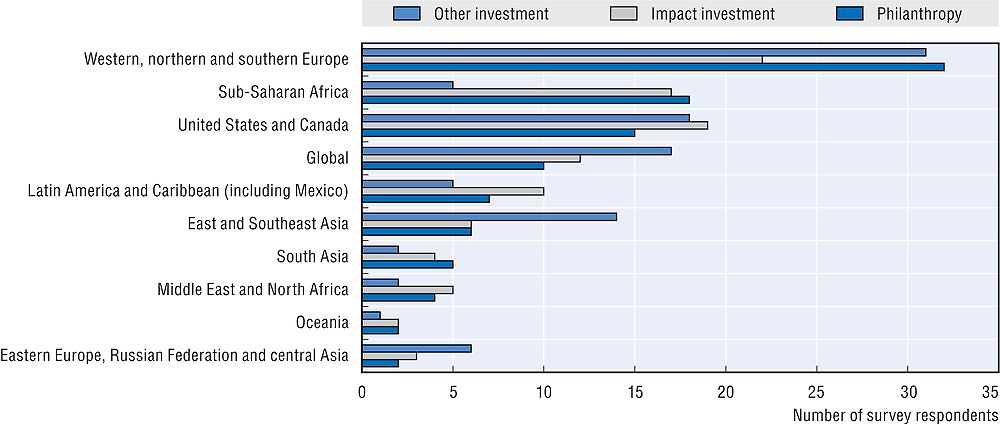

Foundations and family offices have played a critical role in the development of social impact investment (Koh, Karamchandani and Katz, 2012), in parallel to their philanthropies. Figure 5.2 shows the mix of financial investment, social impact investment and philanthropy among foundations and family offices responding to a 2015 Financial Times survey. The data illustrate the growing importance of social impact investment as a core activity for these organisations.

Note: The respondents included 180 foundations and family offices active in either philanthropy or impact investment.

Source: Adapted from Financial Times (2015), Investing for Global Impact 2015, The Financial Times Limited, London.

Foundations are often independent from both government and from markets, which gives them the freedom to take a longer term perspective and to explore and create innovative means of addressing social, economic and environmental challenges. Some foundations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bertelsmann Foundation, have focused on helping to develop the market by supporting research and networks. Others provide “catalytic” capital for social ventures, or actively invest in them using programme-related investments, i.e. investments made out of their endowment in ventures that are related to their core mission. These investments may be made in parallel to the regular grant-making of the foundation and are typically in the form of loans, guarantees or equity investment; their repayments or returns are reinvested in new projects (Rangan, Appleby and Moon, 2011). The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Ford Foundation have pioneered the use of programme-related investments.

Institutional investors are looking increasingly to the developing world

More recently, traditional or mainstream investors – including pension funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors – have begun to demonstrate interest in the social impact investment market in developing countries, despite the associated challenges, such as high risks and relatively costly investment environments (WEF, 2014; Wood, Thornley and Grace, 2012). These investors tend to focus on investments with financial returns that are commensurate with the higher risks (WEF, 2013). Banks and private equity funds may also provide capital to businesses that are expected to generate a profit in social sectors, including education, health (Box 5.2) and nutrition.

In India, 70% of the population is semi-urban and rural, yet 80% of the country’s healthcare facilities are in urban areas.

Source: Annual survey conducted by J.P. Morgan and the Global Impact Investing Network of 145 impact investors (2015), “Eyes on the horizon: The Impact Investor Survey”, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and the Global Impact Investing Network, https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/2015.04%20Eyes%20on%20the%20Horizon.pdf.

Many of the world’s poor are excluded from decent health services. Current estimates suggest that in order to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all, at all ages” by 2030 (SDG 3), USD 51-80 billion will be needed in developing countries alone (UN, 2015; Schmidt-Traub and Sachs, 2015).

In India, 70% of the population lives in semi-urban and rural areas and often has no access whatsoever to basic healthcare services; 80% of the country’s healthcare facilities are located in urban and metropolitan areas. Companies such as Vaatsalya Healthcare aim to fill this gap by building and managing hospitals and clinics to provide primary and secondary healthcare services where they do not exist, but where they are needed most.

Initially, Vaatsalya’s founders – doctors Ashwin Naik and Veerendra Hiremath – found it difficult to raise money. While investors were willing to fund business ventures related to information technology, start-up hospitals were not considered worthwhile ventures. Making emotional appeals to friends and relatives, many of whom were from small towns and villages, they were able to raise about USD 150 000 from angel investors to set up a private limited company in November 2004. Today, 40% of Vaatsalya’s equity comes from institutional investors who expect financial returns from their investments in the long run. The founders acknowledge that support from strategic investors has helped to reorient Vaatsalya from a social organisation to a social enterprise, balancing social objectives with financial viability.

For more information see: www.vaatsalya.com.

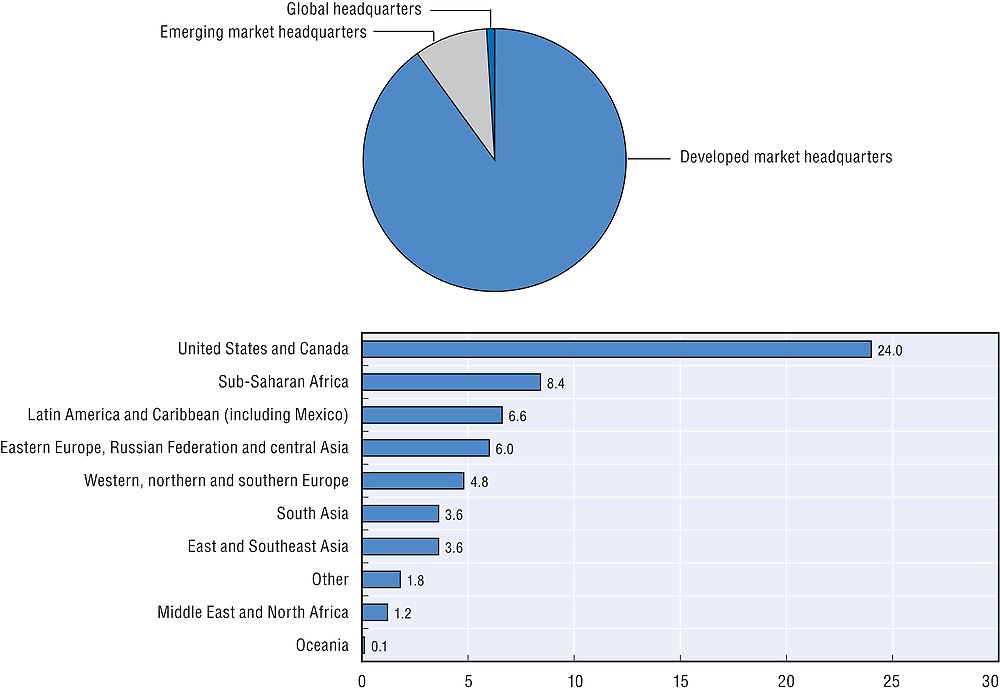

The 2015 annual survey conducted by the Global Impact Investment Network and J.P. Morgan provides an indication of the global investment trends of a growing number of institutional investors engaged in social impact investment. Figure 5.3 shows the geographic location of the headquarters of a sample of these investors, primarily in developed countries, as well as the distribution of their assets.

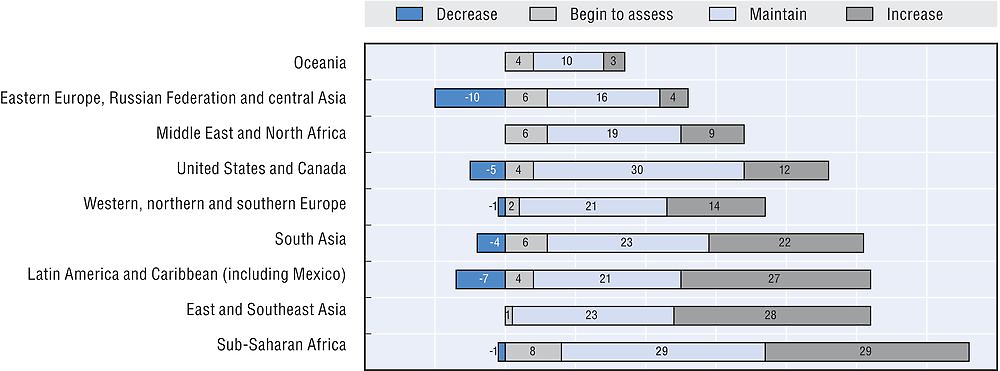

Unlike traditional foreign direct investment, social impact investment is concentrated in frontier (developing or emerging) markets (Simon and Barmeier, 2010). The J.P. Morgan survey also shows that the target regions for social impact investment are increasingly in developing countries, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, east and Southeast Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 5.4).

Note: Ranking by number of respondents who chose “increase” from a survey of 145 impact investors.

Source: Annual survey conducted by J.P. Morgan and the Global Impact Investing Network of 145 impact investors (2015), “Eyes on the horizon: The Impact Investor Survey”, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and the Global Impact Investing Network, https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/2015.04%20Eyes%20on%20the%20Horizon.pdf.

In developing countries, grants and technical assistance can help ventures addressing social challenges to develop commercially viable solutions (Bridges Ventures, 2012). Development finance institutions can play an important role, providing “catalytic” funding or guarantees, and covering some of the administrative costs of investment deals. The World Economic Forum report “Charting the course: How mainstream investors can design visionary and practical impact investing strategies” provides practical guidance for mainstream investors wishing to engage in social impact investment, including on how to evaluate the feasibility of projects, perform sector due diligence, launch pilot programmes and institutionalise impact investment strategies (WEF, 2014).

The social impact investment ecosystem is complex

Social impact investments can be made across countries, sectors and asset classes and can produce a wide range of returns (Bridges Ventures, 2009). They can include results-based financing, outcomes-based approaches, market-based solutions and different forms of public-private partnerships. Often, multiple types of investors provide diverse forms of capital (Box 5.3). This allows investors to address social challenges in more scalable ways than is possible for governments working alone (Rangan, Appleby and Moon, 2011).

Multiple types of investors with diverse forms of capital address social challenges in more scalable ways than can governments working alone.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network estimates that USD 46 billion needs to be invested to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture” (SDG 2, UN, 2015). Agriculture and nutrition are promising areas for social impact investors and are also crucial for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

In Colombia, inefficient supply chains, lack of access to markets and rudimentary agricultural practices translate into low incomes for smallholder farmers. Poor storage and distribution facilities generate high wastage. The Colombian company Siembra Viva is enhancing smallholder agricultural productivity, providing technical assistance and sharing knowledge.* The company helps rural farmers switch from commodities to value-added organic products, offering an online platform that connects them to a consumer base in cities, informing them when to plant and to harvest based on demand projections, and guaranteeing produce purchase at pre-determined, premium prices. In addition, it works to eliminate inefficiencies in the supply chain and to bring down the costs of transportation. In general, Siembra Viva reduces waste from 30% to 5%, helping to raise farmer income proportionally.

The investment power behind Siembra Viva is provided by Acumen, a social venture fund that has invested more than USD 88 million in 82 companies across Africa, Latin America and south Asia. Acumen makes investments in water, health, housing, energy, agriculture and education in the form of loans and equity. Its commitments range from USD 300 000 to USD 2 500 000, with payback or exit in seven to ten years. The fund was founded in 2001 with seed capital from foundations and individuals, including the Rockefeller and Cisco Systems Foundations. Key investors contributing more than USD 5 million include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Robert and Kate Niehaus Foundation, and Unilever.

← * Website: http://siembraviva.com/home (in Spanish).

Source: Acumen, http://acumen.org/investment/siembra-viva.

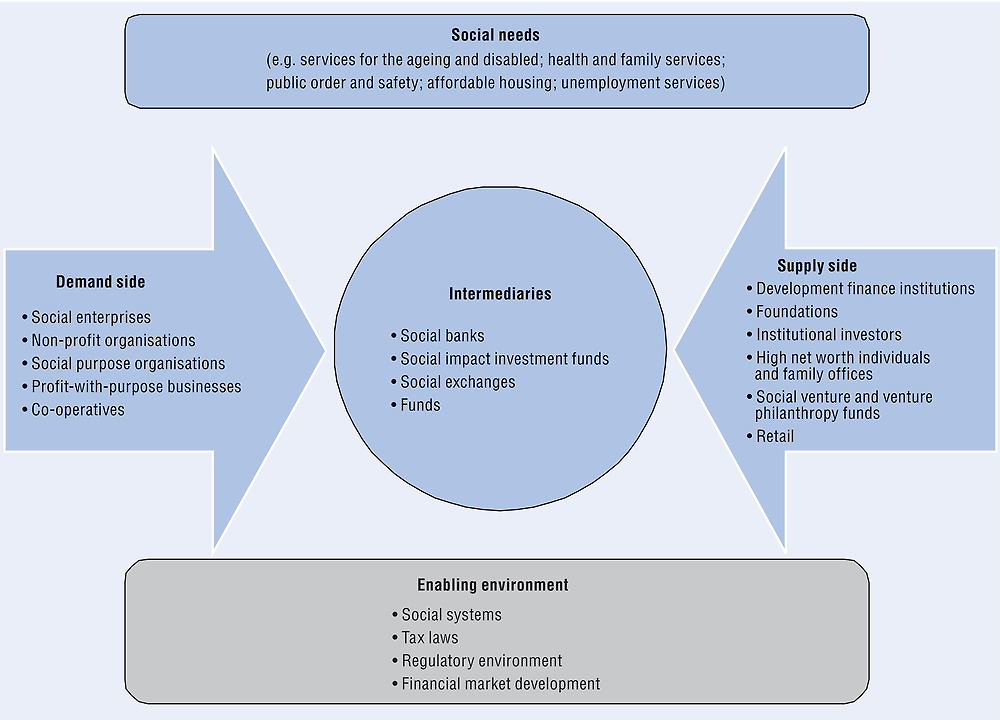

The growing range of actors in the social impact investment market is contributing to a complex framework of investors (supply side), investees (demand side) and intermediaries (Figure 5.5). As in regular financial markets, the intermediaries – such as social banks or social impact investment funds – play a pivotal role in developing the social impact investment ecosystem. They make the links between investors, investees and others, and offer innovative solutions that can help to improve efficiencies, lower costs (e.g. by creating liquidity and facilitating payment mechanisms) and reduce risks (WEF, 2013). They can also offer guidance, and help in structuring deals and in managing funds.

Source: OECD (2015c), Social Impact Investment: Building the Evidence Base, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233430-en.

Similar to other types of investment, the enabling environment for social impact investment is key. The evolution of the social impact investment market in each country is influenced by the country’s history, social needs and value system. The ways in which a country’s social and financial systems are structured also affects the mix of public and private capital, and therefore the potential role of social impact investment. For this reason, varying approaches to facilitating social impact investment are needed, adapted to each country’s needs and circumstances. Careful analysis of contexts and variants can help to determine which social impact investment approaches are best suited to each sector and country. The local diversity of development challenges and needs also makes it important to understand which financial instrument and funding model can be most effective for each social venture and at each stage of development (Evenett and Richter, 2011).

Innovation in social impact investment is flourishing

Diverse experiments and initiatives over the past several years – led by governments, foundations, investors and others in developed and developing countries – are helping to develop new models and approaches (see the “In my view” box by Sonal Shah and Box 5.4). International development agencies are also searching for innovative tools to increase their effectiveness and long-term development impact while working within the limitations of tightening budgets.

Sonal Shah, Professor of Practice and founding Executive Director of the Beeck Center for Social Impact & Innovation, Georgetown University1

In many developing and emerging markets, private sector actors and business models are achieving significant measurable and sustainable impact. Social impact investment offers the opportunity to catalyse and improve private sector investment designed to solve social challenges, to collect and analyse data on what works, to scale up effective programmes and businesses, and to create more robust enabling environments for innovation and entrepreneurship.

When the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister set up the G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce in 2013, I was charged with leading an International Development Working Group to produce recommendations on how governments can catalyse impact investment as a tool for international development. Based on an understanding of the complexity of development and the critical need to leverage private capital (debt, equity and blended instruments), expertise and in-kind investment, the International Development Working Group offered three recommendations:2

-

Create an impact finance facility that can help cultivate and develop new and innovative companies and business models so as to develop a pipeline of investment-ready proposals.

-

Create a development impact bond outcomes fund to facilitate the rollout of pilots worldwide.

-

Improve metrics, increase transparency and provide the additional resources needed to build the broader enabling environment or ecosystem for impact investment.

As the importance of social impact investment grows, there is a need for new business models, financing vehicles, standards and policies to build and bolster ongoing investments, and to bring them to scale.

In my view, meeting the real challenges of scale will require some flexibility or risk taking by local and global investors. This calls for a collective effort to learn from what works and to test new models. The evolution of the microfinance industry is an important reminder of the “thousands of cycles of trial and error” needed to create a successful product (Counts, 2008). This means early investors will need to take on some risk and maybe even forego financial returns to find the best business models and structures to achieve success at scale – thus encouraging larger investors to follow. There is a need to ensure that effective metrics and standards allow investors to continually assess risks.

The capacity of social impact investors to positively affect the lives of the poor and under-resourced people they intend to serve will depend on their ability to innovate, taking existing frameworks forward through dynamic processes that reach large numbers of the poor with products or interventions capable of transforming their lives.

← 1. The author wishes to thank Innocent Obi for his contribution to this box.

← 2. For further information see SIITF (2014a).

The Aavishkaar India Micro Venture Capital Fund targets the low-income market segment of India’s underserved regions. Its investment portfolio spans a range of sectors, including agriculture, education, energy, health, water and sanitation. Aavishkaar makes investments in the form of equity and (short-term) loans ranging from USD 15 000 to USD 1.1 million. In addition, Aavishkaar provides business advisory support. The fund started in 2001 with seed investments by individuals ranging from USD 5 000 to USD 10 000. By 2005, the fund had raised almost USD 1 million, mainly from wealthy individuals who invested up to USD 100 000. From 2005 to 2009, additional capital was raised from foundations, development finance institutions and fiduciary investors.

Aavishkaar’s founding team faced the challenge of adapting the methodology followed in the Silicon Valley to the “brick and mortar” back home: investing in rural geographies whose target clientele had tiny wallets, while delivering reasonable returns to investors. Aavishkaar brought three key innovations to bear:

-

Moving the investment risk from technology and product innovation to innovation in execution.

-

Redefining the parameters of blockbuster success: a return of 5-10 times invested capital, instead of 100.

-

Identifying young and experienced investment managers driven by passion, social recognition and fulfilment from their work.

Source: Aavishkaar website: www.aavishkaar.in.

“Pay-for success” models are drawing increased attention

Outcome-based or “pay-for-success” instruments, such as social impact bonds, were first launched in the United Kingdom several years ago. These public-private partnership models are capturing attention as an efficient way to finance solutions to social issues while contributing to public service delivery. Commissioned by public authorities to achieve social goals through innovation and improved effectiveness in social service provision, the partnerships work to predefined targets and measurable social outcomes (e.g. results, impact and accomplishments). The service providers are often non-governmental organisations or social enterprises with a track record in addressing a particular social need; for example, the Peterborourgh Prison social impact bond enabled the One Service to offer support services addressing the multiple and complex needs of newly released prisoners, helping them to readjust to the community and avoid reoffending.2 Private investors provide the funding and are repaid only when the outcomes, defined a priori by the commissioner of the social impact bond, are achieved. While promising, social impact bonds can also be complex and time consuming to structure and implement (Addis, McLeod and Raine, 2013).

Impact bonds can contribute to development effectiveness

Building on the social impact bond pay-for-success model, development impact bonds are focused on producing results in developing countries. They seek to improve the effectiveness of development co-operation by shifting the focus from the quantity of the investment onto the quality of implementation and the delivery of successful results. Yet unlike social impact bonds in developed countries, the typical commissioner of development impact bonds is not a local government, but rather an international organisation or development agency. For example, the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development has been working on a development impact bond for the prevention of deadly sleeping sickness in Uganda.3 The participation of private sector actors, who may be better positioned than the public sector to take on the risks associated with innovation, is key.

While social and development impact bonds have attracted a lot of attention, there are new outcome-based models being developed, including outcome funds (Box 5.5), social impact notes and other streamlined pay-for-success mechanisms.

Over USD 120 billion is spent annually on education in low and middle-income countries, yet education outcomes in many places remain poor. There are still 58 million children who never attend primary school and 65 million adolescents who don’t attend secondary school. Furthermore, 130 million children remain in primary school for four years without reaching minimal benchmarks – in other words, without the basic skills and knowledge that would enable them to improve their lives and benefit their countries’ economies.

Traditional grant-based education models have struggled to improve student outcomes. The international community has shifted away from a funding approach that places emphasis on inputs to an outcomes-based approach (Pritchett, Banerji and Kenny, 2013). Outcomes funding, if implemented well, can create incentives for service providers and governments to innovate and scale up interventions in ways that enable them to deliver the best outcomes, and to deploy limited resources effectively.

The Global Social Impact Investment Steering Group (GSG), established in August 2015 as the successor to the G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce, is partnering with the new International Commission for Education chaired by Gordon Brown. It has given Social Finance UK* a mandate to establish the USD 1 billion Outcomes Fund for Literacy to improve educational outcomes in developing countries.

A number of independently managed development impact bond funds will complement the Outcomes Fund, backing non-governmental organisations and businesses capable of implementing effective programmes, crowding in private investors, and thereby accelerating the flow of funding to service delivery organisations addressing literacy in developing countries.

← * Social Finance UK is a not-for-profit social investment organisation in the United Kingdom that partners with government, the social sector and the financial community to create better ways of tackling social issues.

Source: Social Impact Investment Taskforce proposal, July 2015, www.socialfinance.org.uk/about-us/#sthash.xvzFm3mx.dpuf.

Measurement of social impact is key

Agreeing on expected outcomes helps make a social enterprise attractive to investors. Effective, robust and repeatable measurement of social impact is critical, as investors want to see that the interventions they support are having the intended impact.

Effective, robust and repeatable measurement of social impact is critical.

Nonetheless, the measurement of social benefits is difficult, and the process of tracking and measuring social returns can be costly in terms of time and resources (Box 5.6). The specific objectives of measurement can also differ for various stakeholders, affecting the measures chosen to track progress and adjust course as needed. Further work will need to be done, probably by intermediaries, to strengthen investor understanding of the variety of impact measurement tools currently available and how best to use them (E.T. Jackson & Associates, 2012).

Measuring social and environmental impact can help enterprises monitor and improve their performance in addressing social issues while also enabling them to access capital markets more effectively. Transparency and accountability, for financial as well as social and environmental impact, can facilitate access to funding from private and public investors.

There are, nonetheless, a number of challenges that derive from the pressures on social enterprises to target a “triple bottom line” (creation of social, economic and environmental value) while balancing the interests of multiple stakeholders (Epstein and McFarlan, 2011; Dart, Clow and Armstrong, 2010). At the same time, as the focus on measuring social impact is relatively new, a shared understanding of how to do it is still evolving. Even so, an increasing number of impact measurement approaches are emerging.

The Impact Measurement Working Group of the Social Impact Investment Taskforce recommends measuring impact by analysing the causal links within the “impact value chain” – e.g. identifying a link between input and intended result – as well as by developing a standardised impact measurement and reporting system (IMWG, 2014). The European Commission’s Expert Group on Social Enterprise calls for measurement of a variety of social impacts and cautions about the premature development of a single methodology (GECES, 2014). There are also metrics systems, such as the Global Impact Investing Rating System (IRIS), which include a large set of possible indicators. However, these can be complex to apply.*

Further research is needed to evaluate existing metrics and methods. This could contribute to the development of an outcomes matrix with an accompanying open-source library of indicators for social enterprises, and to the establishment of a knowledge centre providing practical help.

In addition to methodological challenges on how to measure impact empirically, other practical challenges remain. In particular, social enterprises, and especially the small ones, often lack the capacity and human and financial resources to implement measurement tools. It is important to ensure that:

-

social reporting requirements are not overly burdensome for social enterprises

-

social enterprises have adequate resources and capacities to measure impact

-

measurement contributes to decision making, and the cost of measurement does not outweigh the importance of the decision.

← * For further information see SIITF (2014b).

Source: Based on European Commission/OECD (2015), Policy Brief on Social Impact Measurement for Social Enterprises: Policies for Social Entrepreneurship, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, www.oecd.org/industry/Policy-Brief-social-impact.pdf.

Effective measurement includes moving from inputs to outcomes, as well as developing means of assessing direct as well as indirect impact. To date, the measurement of social impact is still largely focused on inputs and outputs – for example, the number of children educated. The measurement of outcomes is much more difficult and requires specifically tailored approaches that can meet the needs of investors while not overburdening the social venture. The development of standard social impact measurement systems will be important for further engaging mainstream investors (HM Government, 2013). At the same time, it is critical to help service providers in all relevant sectors develop their capacity to measure social outcomes (Addis, McLeod and Raine, 2013).

The measurement of the direct social impact of a project is important in enabling the enterprise and investors to determine if the targeted results are being achieved. However, a better understanding of the broader impact of social impact investment (including spillover effects and positive externalities) around the world is also essential to fully determine the results of social impact investment and assist in policy decision making.

It is crucial to build an evidence base on what is working.

Building an evidence base on what is working will ensure that capital is invested in interventions that will achieve the intended impact. This means systematically collecting and using data in a cross-country comparable way, in particular in developing countries, where the bulk of social impact investments are being made. Analysis and case studies of a variety of instruments and sector-specific investments can help to clarify the roles of the various actors and processes involved in structuring social impact investment. In turn, a better understanding of the successes and failures of different approaches can help to identify which social impact investment models work best in each country and context, and to scale up successful cases.

It is also fundamental to develop a better understanding of the roles, motivations and financing mechanisms of different types of investors, especially in today’s increasingly diversified development finance framework. Monitoring and measurement are key. New approaches to measurement, such as the total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD) framework (Chapter 4), will help to capture the full spectrum of financial instruments and the range of sources of financial flows. This should also facilitate analysis of the trade-offs involved with various types of financing, as well as which market settings are appropriate for each type of financing.

The way forward for social impact investment

Social impact investment can provide new ways of efficiently and effectively using public and private capital to address social and economic challenges at the global, national and local levels. It provides a vehicle for bringing innovation to existing delivery mechanisms, offers important market-based approaches that can have an impact where it is most needed, and creates incentives for more rigorous measurement of development outcomes.

As highlighted by Julie Sunderland in her challenge piece at the start of this chapter, social impact investors can address the needs of the poorest populations by aligning their social and financial goals, creating new business models, and developing entrepreneurial talent in the local community. The public sector can play an important role in promoting social impact investment, providing risk capital to “support innovative models that provide affordable, accessible, quality products and services to bottom-of-the-pyramid populations”.

The OECD Policy Framework for Investment (see Chapters 2 and 6) can facilitate social impact investment in developing countries by contributing to the development of vibrant entrepreneurial markets and strong enabling environments (OECD, 2015b). The framework is already supporting sound investment policies in some 30 developing and emerging economies around the world, helping to put in place policy reforms that encourage more investment in social and environmental impact, alongside financial returns.

Despite the fact that social impact investment is still relatively new, it is already producing results on the ground in developing countries. The examples in this chapter provide a snapshot of ways in which non-state providers are successfully delivering services that respond to the needs of bottom-of-the-pyramid populations. They illustrate how the demand for financing that addresses social needs is growing, and how providing solutions to development challenges can offer new and potentially profitable investment opportunities for social impact investors. Yet much remains to be done to match funding with investment opportunities to generate financial as well as social returns. The recommendations below can contribute to realising this potential.

Key recommendations for getting social impact investment right

-

Advance knowledge of social impact investment instruments and their applicability in the context of the 2030 Agenda, in a variety of sectors and across different country settings.

-

Promote international research, data collection, case studies and the development of indicators on social impact investment.

-

Increase transparency and provide the additional resources needed to build the broader enabling environment or ecosystem for impact investment; ensure that social reporting requirements are not overly burdensome for social enterprises.

-

Cultivate and develop new and innovative companies and business models, including ones adapted to the needs of the bottom-of-the-pyramid populations.

-

Develop local entrepreneurial talent and a pipeline of investment-ready project proposals and facilitate the roll-out of pilots worldwide.

-

Build an evidence base on the impacts, outcomes, successes and failures of social impact investment in ways that are comparable across countries.

-

Align incentives for social and financial goals, and help service providers develop their capacity to measure social outcomes.

-

Use new approaches to measurement, such as the TOSSD framework, to capture and evaluate the full spectrum of financial instruments and sources.

-

Use public funds to:

-

strengthen the overall governance framework to ensure a sound business environment in developing countries, in particular in the least developed countries and in countries emerging from conflict

-

leverage private funds by providing incentives and/or helping to reduce risks via guarantees or early-stage grants or investment

-

help to develop the social impact investment ecosystem to ensure a well-functioning market

-

establish platforms to exchange knowledge and share experiences among development actors and the social impact investment sector.

-

References

Addis, R., J. McLeod and A. Raine (2013), IMPACT – Australia: Investment for Social and Economic Benefit, Australian Government, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Canberra, https://docs.employment.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/impact-australia_nov_2013_2.pdf.

Bannick, M. and P. Goldman (2012), “Priming the pump: The case for a sector based approach to impact investing”, Omidyar Network, London, http://tinyurl.com/jhnjm6b.

Bridges Ventures (2015), “The Bridges spectrum of capital: How we define the sustainable and impact investment market”, Bridges Ventures, London, http://bridgesventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Spectrum-of-Capital-online-version.pdf.

Bridges Ventures (2012), “Sustainable & impact investment: How we define the market”, Bridges Ventures, London, http://tinyurl.com/h5o5jql.

Bridges Ventures (2009), “Investing for impact: Case studies across asset classes”, Bridges Ventures, London, http://bridgesventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Investing-for-Impact-Report.pdf.

Counts, A. (2008), Small Loans, Big Dreams: How Nobel Prize Winner Muhammed Yunus and Microfinance are Changing the World, Wiley.

Dart, R., E. Clow and A. Armstrong (2010), “Meaningful difficulties in the mapping of social enterprises”, Social Enterprise Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 186-193, https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611011088797.

Epstein, M.J. and F.W. McFarlan (2011), “Measuring the efficiency and effectiveness of a non-profit’s performance”, Strategic Finance, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 27-34.

E.T. Jackson & Associates (2012), “Accelerating impact: Achievements, challenges and what’s next in the impact investing industry”, The Rockefeller Foundation, New York, www.rockefellerfoundation.org/report/accelerating-impact-achievements.

European Commission/OECD (2015), Policy Brief on Social Impact Measurement for Social Enterprises: Policies for Social Entrepreneurship, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, www.oecd.org/industry/Policy-Brief-social-impact.pdf.

Evenett, R. and K. Richter (2011), “Making good in social impact investment: Opportunities in an emerging asset class”, The Social Investment Business and TheCityUK, www.engagedx.com/portfolio_making-good-in-social-impact-investing.html.

Financial Times (2015), Investing for Global Impact 2015, The Financial Times Limited, London.

GECES (2014), “Proposed approaches to social impact measurement in the European Commission legislation and practice relating to: EuSEFs and the EaSI”, GECES Sub-group on Impact Measurement, June, http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/social_business/docs/expert-group/social_impact/140605-sub-group-report_en.pdf.

HM Government (2013), “G8 Social Impact Investment Forum: Outputs and agreed actions”, Cabinet Office, London, http://tinyurl.com/oso528p.

IMWG (2014), “Measuring impact: Subject paper of the Impact Measurement Working Group”, Social Impact Investment Taskforce, September, www.socialimpactinvestment.org/reports/Measuring%20Impact%20WG%20 paper%20FINAL.pdf.

J.P. Morgan and the Global Impact Investing Network (2015), “Eyes on the horizon: The Impact Investor Survey”, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and the Global Impact Investing Network, https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/2015.04%20Eyes%20on%20the%20Horizon.pdf.

Koh, H., A. Karamchandani and R. Katz (2012), “From blueprint to scale: The case for philanthropy in impact investing”, Monitor Group and Acumen Fund, http://tinyurl.com/j7jqxxe.

OECD (2015a), Development Co-operation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2015-en.

OECD (2015b), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en.

OECD (2015c), Social Impact Investment: Building the Evidence Base, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233430-en.

OECD (2014), Development Co-operation Report 2014: Mobilising Resources for Sustainable Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2014-en.

Pritchett, L., R. Banerji and C. Kenny (2013), Schooling is Not Education! Using Assessment to Change the Politics of Learning, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/schooling-is-not-learning-WEB.pdf.

Rangan, K.V., S. Appleby and L. Moon (2011), “The promise of impact investing”, Background Note, No. 512-045, Harvard Business School, Boston, www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=41512.

Schmidt-Traub, G. and J.D. Sachs (2015), “Financing sustainable development: Implementing the SDGs through effective investment strategies and partnerships”, working paper prepared for the Third Conference on Financing for Development, Addis Ababa, 13-16 July 2015, United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, http://tinyurl.com/za8yvgy.

SIITF (2014a), “International development”, subject paper of the International Development Working Group, Social Impact Investing Taskforce, http://tinyurl.com/zk3gbd4.

SIITF (2014b), “Measuring impact”, subject paper of the Impact Measurement Working Group, Social Impact Investing Taskforce, http://tinyurl.com/z336man.

SIITF (2014c), “Allocating for impact”, subject paper of the Asset Allocation Working Group, Social Impact Investing Taskforce, http://tinyurl.com/j4vbz7r.

Simon, J. and J. Barmeier (2010), More than Money: Impact Investing for Development, Center for Global Development, London, www.cgdev.org/publication/more-money-impact-investing-development.

Swiss Sustainable Finance (2016), “Swiss Investments for a Better World. The First Market Survey on Investments For Development”, April.

UN (2015), “Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, United Nations, New York, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

UNDP (2014), “Impact investing in Africa: Trends, constraints and opportunities”, Working document, United Nations Development Programme, New York, www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/Partnerships/Private%20Sector/Impact%20Investment%20Final%20Report.pdf.

WEF (2014), “Charting the course: How mainstream investors can design visionary and practical impact investing strategies”, World Economic Forum, Geneva, www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_ImpactInvesting_Report_Charting TheCourse.pdf.

WEF (2013), “From the margins to the mainstream: Assessment of the impact investment sector and opportunities to engage mainstream investors”, World Economic Forum, Geneva, www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_II_From MarginsMainstream_Report_2013.pdf.

Wilson, K.E. (2014), “New investment approaches for addressing social and economic challenges”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 15, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jz2bz8g00jj-en.

Wood, D., B. Thornley and K. Grace (2012), “Impact at scale: Policy innovation for institutional investment with social and environmental benefit”, Insight at Pacific Community Ventures, Institute for Responsible Investment at Harvard University and Rockefeller Foundation, https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20120221220232/Impact-at-Scale_Full-Report.pdf.

Notes

← 1. A special thanks to Julia Sattelberger and to Wiebke Bartz from the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate for, respectively, help with the boxes and examples in the chapter; and with the background data and the case studies.

← 2. For further information see: www.socialfinance.org.uk/impact/criminal-justice.

← 3. For further information see: https://devtracker.dfid.gov.uk/projects/GB-1-203604 and www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-development-bonds-will-combat-global-poverty.