Finnish architecture and design: A natural fit

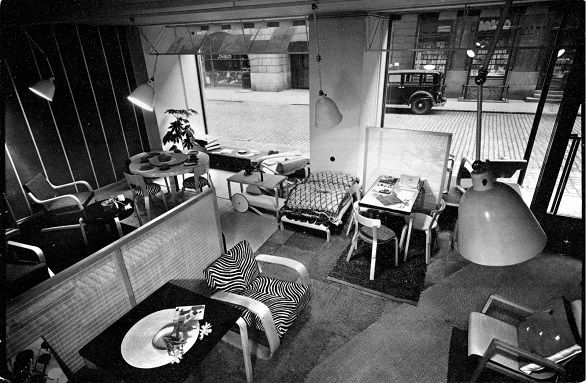

First Artek shop in Helsinki, 1936; photo provided especially to OECD Observer by Artek.

Finland has a reputation among designers, architects and artists for being a land, a nation, a culture that produces high-quality design and architecture. It tops happiness polls and educational surveys, can produce determined sports champions, and world-class high-tech products and games software, but it also has a relatively high incidence of mental illness and has been battling down its suicide rate. A land of extremes with a wide breadth of emotions, talents and expectations?

What is the secret of this small nation’s success? People, their customs and their local habits are often expressions of an existential struggle with the natural settings they are born in. In Finland the extreme cold and darkness of winter, the long days of light in summer, the deep cool lakes, the secretive beauty of the forests, are dramatic character and soul forming elements. Can the Finnish success in the design world be linked to the workings of such poetic forces? Or is it linked to the instinctive strength of character (what Finns call sisu) born out of Finland’s vast lonely expanses and living at a healthy distance from busy European metropoles?

In my visits to Finland, Helsinki, Turku, Tampere and Vaasa, I experienced the quiet, humble confidence of these admirable people. Coffee drinking, one of my favorite educational passtimes, provided me with many venues for my research and moments of reflection as I got to know this special land. As a designer I am accustomed to recognising in a space when, in the simplest of ways, harmony and balance can be expressed in the interaction of single elements, producing a sense of whole. Spaces that achieve this level of coherency have no superfluous elements. What I see is a simple, understandable code being used, with nothing redundant in the composition: the trees have leaves in summer, the water is ice in winter, the wood is preferred in natural tones, the light temperature used is warm, the cups simple and undecorated. Humanity’s work and that of nature are one.

Alvar Aalto, a Finnish architect from the last century and a younger member of the old school of early moderns, such as Le Corbusier or Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, is a stimulating figure that I use in my teaching to explain the importance of holistic thinking to a generation that has been overwhelmed by the false promises of specialisation and virtual visualisations.

Aalto and his wife Aino (also an architect whom he met in 1924) worked as a team on several projects together, and in 1935 founded the furniture and lighting firm Artek (www.artek.fi). They believed in holistic thinking, art and technology, small and big, and that the house should be designed “from the doorstep to the living room.”

Aalto and Aino believed in the social importance of their profession, developing simple and inspirational works of architecture that the layperson could appreciate and enjoy. They also worked across all the scales, from furniture design to large public buildings. Furniture was not just a marketing vehicle to them, it was an area of design where the human scale and needs could be expressed in unison with natural materials. Aalto experimented with bending wood to form a natural structural entity to seat the human form with minimal waste of materials. In this micro-architectural exercise we witness how humans can tame nature to express being at one with our environment. Aalto’s architecture is an extension, if not a re-interpretation, of the nature around us. The search for the symbiosis between humans, nature and technology is evident in the works he produced.

Aalto, who was rational and practical in his thinking process and construction of space, did not shy from using the symbolic and mythological powers of his national spirit. In his famous design for the Finnish Pavilion, for the New York World’s Fair in 1939, Aalto constructed a surging leaning wall of wood, which evoked images of a Finnish forest housing images of Finland in an undulating flowing line that counters the orthogonal line of the supporting service buildings. This is Aalto’s code, simple and complex, soft and hard. Perhaps this is Finland’s code.

Another much-loved work of Aalto is his glass vase from 1936. The vase gives us the undulating line he used later in his Finnish pavilion, and which implies capturing dynamic change as the wind moves the face of a forest in the sun or causes ripples in the water of the lakes. Such lines can also be seen in the structure of split rocks or in the grains of cut trees. In small objects and in big architecture, Aalto proves that the complexity of life is hidden in simplicity, for all who look. In the coffee shops, I understood this as I sat on Aalto stools, designer stools that formed part of a bigger Finnish code.

Ruairí O’Brien, an architect based in Germany, has worked in Finland. He currently teaches in Cairo.

See also “Japan’s radiant architecture”, in OECD Observer No 298, Q1 2014, at https://oe.cd/obs/2Ay

This article is part of a series celebrating Finland's 50th anniversary as a member country of the OECD: www.oecdobserver.org/finland50oecd

©OECD Observer 317-318, Q1-Q2, June 2019