Working for the recovery

The crisis has had a huge impact on jobs and may have changed the labour market forever. John Martin, OECD Director of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, explains the challenges facing policymakers in the years and decades ahead.

OECD: What impact has the crisis had on unemployment?

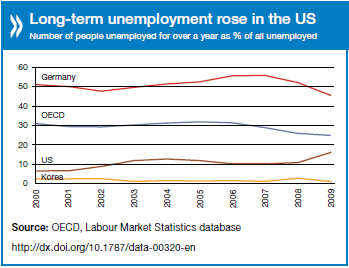

John Martin: The crisis is unlike anything we’ve experienced before. The oil crisis of the early 1970s led to massive hikes in unemployment in almost all OECD countries. This time the impact has been very different from country to country. At one end of the spectrum, there’s been almost no increase in unemployment in countries like the Netherlands, Norway, Austria, Switzerland and Korea where joblessness is still at 3 to 4%. In Germany, unemployment has actually fallen. At the other end, more than one in five Spaniards in the labour force are out of work. Countries have also reacted in very different ways. In some, firms have carried out massive layoffs, like in Ireland, Spain and the United States. In others, firms have kept workers on the payroll but put them on shorter working hours. We’ve seen that in Belgium, Germany, France and Italy, and also outside Europe, in Japan and Korea.

Have labour laws been found wanting in any way?

The crisis has definitely raised a debate around labour laws that protect workers rather than jobs. The best illustration is Spain. It has traditionally had very high protection for workers on permanent contracts and much less for people on temporary contracts. This led to a growing dualisation of the labour market, also found in some other European countries like Italy, France and Greece. The OECD has been arguing for many years that it’s desirable to shift that balance: on the one hand there ought to be less protection for permanent workers and more for temporary workers–backed at the same time by a much more effective activation strategy. The Spanish government did not grasp this nettle before the crisis, but now it has moved significantly in that direction with its most recent reforms. In a sense the crisis highlighted the problem, and the markets and public opinion forced a change.

Some people are saying that European countries with less flexible labour markets, like Germany, seem to have come out better than more flexible countries like the US. Would you agree?

That comparison is overdrawn. There’s no doubt that the way in which collective bargaining, unions and employers responded to the crisis in Germany was very different than in the US. That’s due a lot to history, and the strengths of unions and employer associations and their ability to work together. But at the same time the German labour market became much more flexible in the years leading up to the crisis, and in particular the reforms by the Schroeder government, the so-called Hartz reforms, really did make a difference by making the labour market more flexible, and encouraging unions and employers to be more consensual in their negotiations when the crisis hit the economy in 2008.

With regard to the US, there are very few short-time working schemes in place, so it’s not surprising that when the crisis hit, firms laid off workers in large numbers. A key issue is how quickly they will start to rehire. The economy has been in recovery for over a year, but the private sector has yet to start rehiring in anything like sufficient numbers to make inroads into the unemployment rate, which is stuck around 9.5%

The real worry is that many of those people have been out of work for a long time: currently over 40% have been unemployed for over 6 months, close to a post-war high. There are two sides in this debate: one school of thought, exemplified by Narayana Kocherlakota, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, says the main problem is that there has been a mismatch in the US economy between the skills that firms want and the skills that unemployed people have. On the other hand, economists like Paul Krugman are saying that there’s always been some degree of skills mismatch, but in the current circumstances it’s the drop in demand which has been the main cause of high unemployment. I have more sympathy with the Krugman school, at least in the short run. But the more entrenched high unemployment remains, the more the skills of those unemployed people atrophy, and the more difficult it is for them to be competitive in the labour market once firms start hiring again. And then you have high unemployment becoming structural, meaning that even an upturn won’t make rapid inroads into reducing unemployment, and that’s the real risk in the US at the moment.

When do you think the jobs situation will start to improve?

We really need to see when, as we all hope, the recovery becomes more robust. That’s going to depend to some extent on resolving several problems in financial markets, government budgets, global trade issues and so on. But let’s assume the world economy recovers more strongly than at present. The countries that have seen the biggest rises in unemployment will face a new challenge in trying to bring it down to more acceptable levels. Past experience tells us that when you have big, sudden jumps in unemployment, it usually takes five to ten years to unwind much of that jump. And even when you do, in some cases you never get back to pre-crisis levels of unemployment. You actually come out of a crisis with a higher underlying rate of unemployment, and that’s a big risk for countries like the US, Ireland, Spain and Iceland right now. In the US even the most optimistic commentators are talking about five years or more to get back to an unemployment rate of 5%. Many of these workers will find another job, but some could end up unemployed for years to come.

If we look further ahead, what other issues in the job market need to be tackled?

Skills. Over the medium term, this is going to become very important. It’s been overshadowed by the immediate effects of the crisis but looking ahead, particularly in the context of ageing populations and workforces and the rise of emerging economies, the OECD countries must continue investing in developing their skills. They are going to have to sort out mismatches in skills embodied in the workforce and the skills firms are demanding. That means putting more emphasis on skill formation and taking lifelong learning much more seriously as a policy goal.

The sad fact is that most investment in skilling ends by the time people are in their late 30s. In the future OECD countries will need to invest much more in mid-career, say in the 40-55 age bracket. That’s going to be a big challenge for OECD countries for the next decade or two, and governments need to get the message across to workers that they need to think constantly about upgrading the value of their skills.

©OECD Yearbook 2011

OECD (2010), Employment Outlook 2010, www.oecd.org/els/employment/outlook

OECD Insights (2010), “Jobs–a continuing crisis”, http://oecdinsights.org/2010/07/16/jobs-%E2%80%93-a-continuing-crisis

OECD Education Policy Forum: Investing in Skills for the 21st Century, 4-5 November 2010 www.oecd.org/education/ministerial/forum