Financial regulation after the crisis: Still liberal, but…

In a report issued in June 2017, the Trump administration laid out its proposal for overhauling some of the regulations President Obama had enacted with a view to avoiding a financial market meltdown of the kind we saw in 2008. But what do we actually know about how financial regulation has evolved around the world since the global financial crisis?

Bank supervision has certainly been an active area of reform, not only in the US, but in many other countries. The Basel III accord, the new international regulatory framework for banks that is currently being rolled out, is one well-known testimony. Some countries took less well-publicised action to tighten up supervision, not least when oversight existed institutionally but failed to function properly in practice.

Financial policy, however, goes much beyond bank supervision. It also includes aspects such as credit controls, ease of entry into the banking sector, capital account controls and government ownership of banks. The general picture of the 30 years leading up to the crisis was one of liberalisation in domestic and international capital markets, accompanied by efforts to strengthen frameworks for bank supervision. But the various dimensions of financial policy are rarely assessed together, even though they all matter for financial markets, corporations and households.

This is precisely what we have set out to do, as we explain in our new OECD working paper. In fact, we have assembled a novel dataset on financial policies from 2006 to 2015 by building on an index from the International Monetary Fund. The index by the IMF is the most widely used measure of financial reforms in cross-country empirical research, having been used in some 200 publications. The trouble is the IMF dataset was only available up to 2005–so we have effectively extended it by another 10 years. The index has its strength in covering many different types of financial policies, though it is not overly specific on most dimensions.

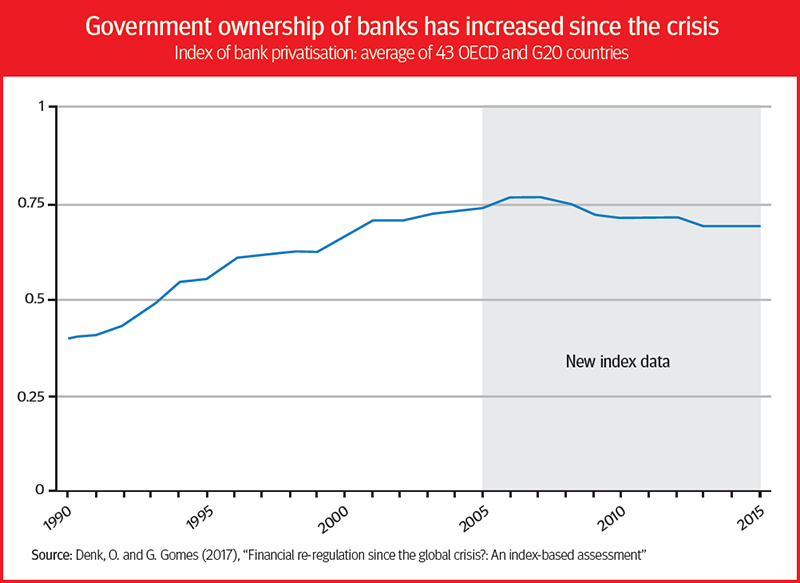

What do we find? In some areas, financial policy has become less liberalised since the global crisis. Bank privatisation has seen the strongest break in trend. Governments reduced their ownership in banks over the one to two decades before the crisis. But since then, recapitalisations in a number of countries have increased government ownership and lowered financial liberalisation in this respect, as our charts show.

In other areas, financial liberalisation has more or less stayed the same. Take restrictions to international capital movements. By standard measures, these had largely gone in most advanced economies before the crisis. Today, the developed world as a whole is as financially open as 10 years ago. However, some countries such as Chile, Iceland and Slovenia have tightened their capital account restrictions, even if others like Australia, Korea and Turkey have lifted theirs.

Bank supervision efforts continued to strengthen through the 2000s under the Basel accords. In many countries, this has not only changed how capital requirements are set, but also reinforced the way in which supervisory authorities assess prudential reports and statistical returns from banks through on-site and off-site examinations.

On the whole, our data suggest that the financial crisis has not undone the financial liberalisation that was achieved in the preceding three decades or so. However, it remains to be seen whether the renewed state ownership of banks is part of a temporary post-crisis phenomenon or something long term . Governments do tend to sell off their stakes in banks when they find the opportunity, and a few countries–Austria is a good example–have now unwound their increased ownership in banks, in some cases thanks to liquidation.

Developments have been quite different for emerging market economies, in particular the BRIICS countries*, where financial liberalisation has continued at the same quite rapid pace as before the global crisis. One reason is that entry barriers into the banking sector have been lowered in some cases; other factors include stronger bank supervision and the deregulation of stock markets. Finance nevertheless remains substantially less liberalised in the BRIICS than the OECD (see second chart).

These are just some of the revelations of our new data, which will hopefully allow the many researchers who have been relying on the IMF dataset for quantifying financial policies to delve into an additional 10 years of observations. This is vital for tracking how policy has affected financial systems and the real economy since the crisis.

If you are such a researcher and would like to use the dataset, please contact us at [email protected] and [email protected].

*BRIICS countries include Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, South Africa Share this article at http://oe.cd/207. It originally appeared on OECD Insights blog, www.oecdinsights.org, 29 June 2017.

Financial re-regulation since the global crisis? https://doi.org/10.1787/0f865772-en