1. General assessment of the macroeconomic situation

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to exert a substantial toll on economies and societies. Prospects for an eventual path out of the crisis have improved, with encouraging news about progress in developing an effective vaccine, but the near-term outlook remains very uncertain. Renewed virus outbreaks in many economies, and the containment measures being introduced, have checked the pace of the global rebound from the output collapse in the first half of 2020, and are likely to result in further near-term output declines, particularly in many European economies. This pattern is likely to persist for some time, given the significant development and logistical challenges in deploying a vaccine widely around the world. Living with the virus for at least another six to nine months will prove challenging. Local outbreaks are likely to continue and will have to be addressed with targeted containment measures if possible, or full economy-wide lockdowns if necessary, which will hold down growth. Some businesses in the sectors most exposed to these continued containment measures may not be able to survive for an extended period without additional support, raising the risk of further job losses and insolvencies that hit demand throughout the economy.

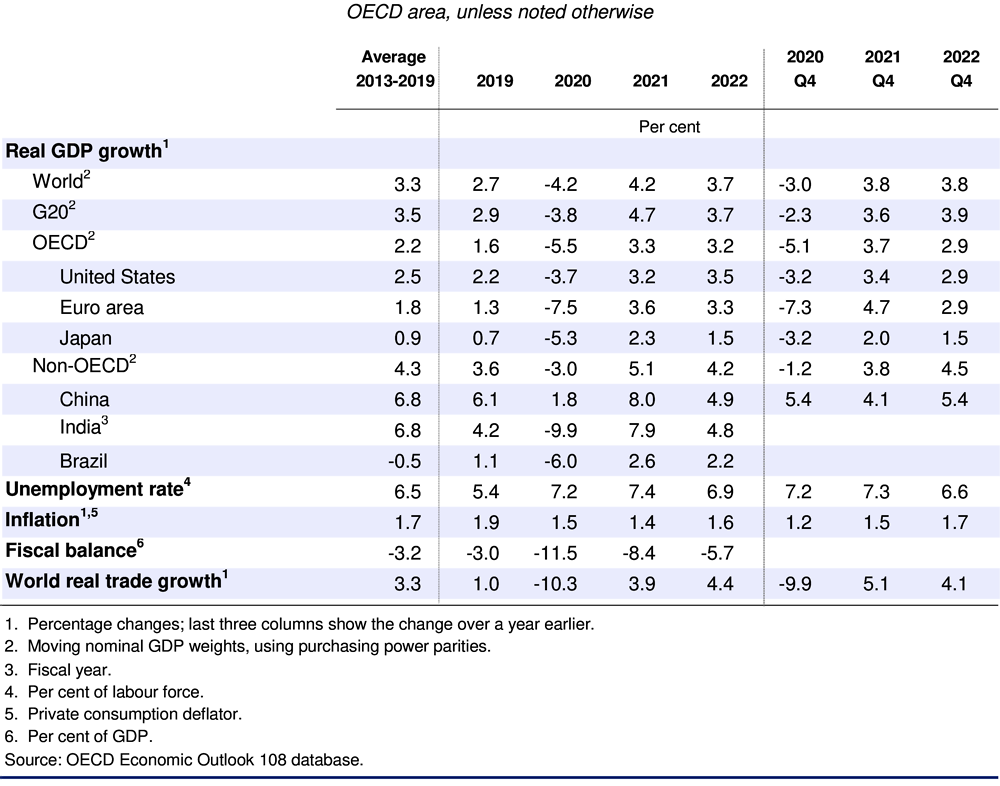

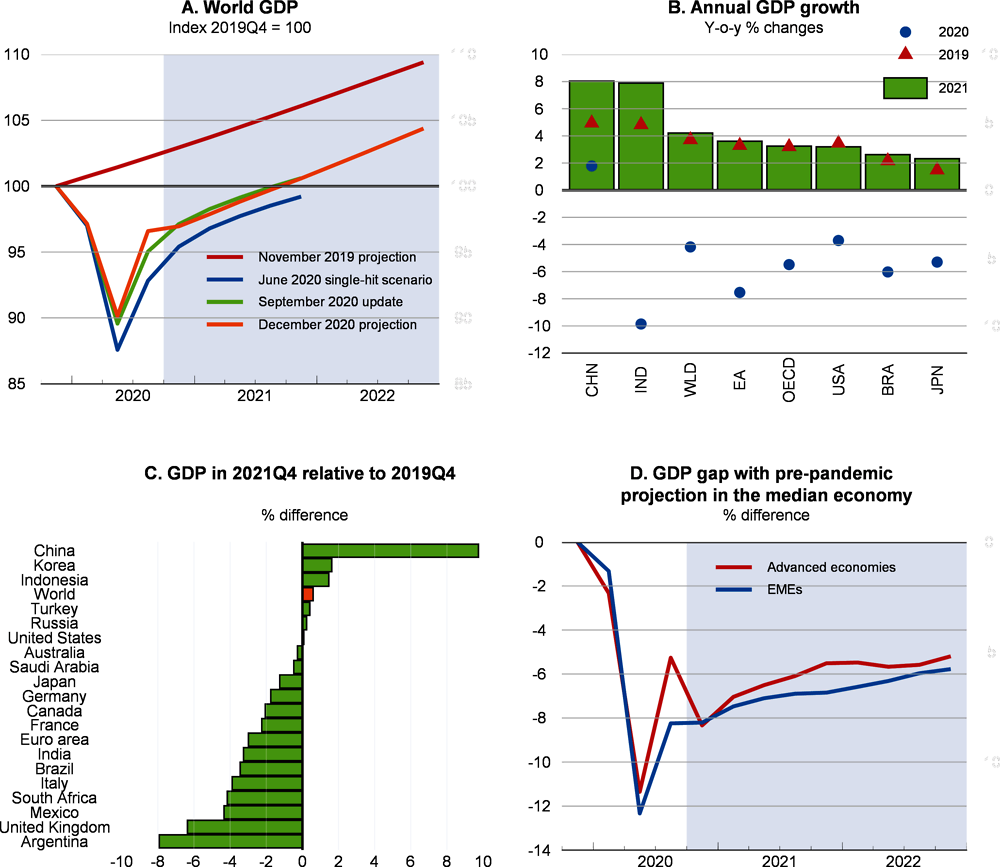

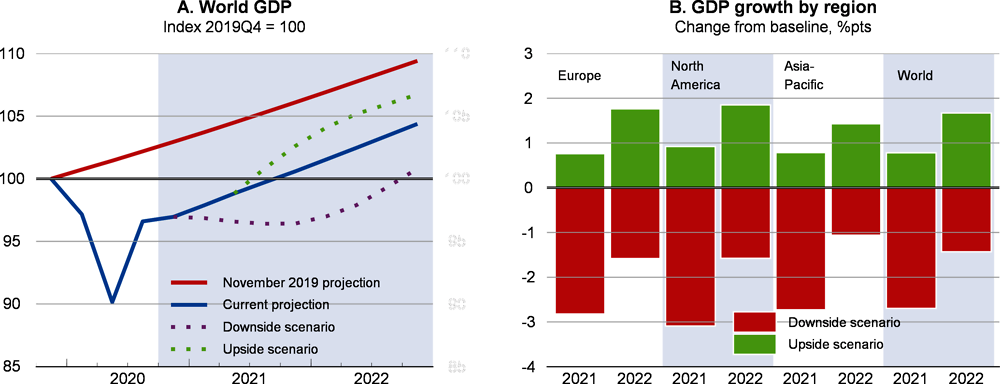

On the assumption that renewed virus outbreaks remain contained, and that the prospect of a widely available vaccine towards the end of 2021 helps to support confidence, a gradual but uneven recovery in the global economy should occur in the next two years (Table 1.1). After a strong decline this year, global GDP is projected to rise by around 4¼ per cent in 2021, and a further 3¾ per cent in 2022. Overall, by the end of 2021, global GDP would be at pre-crisis levels, helped by the strong recovery in China, but performance would differ markedly across the main economies. Output is projected to remain around 5% below pre-crisis expectations in many countries in 2022, raising the risk of substantial permanent costs from the pandemic. Countries and regions with effective test, track and isolate systems are likely to perform relatively well, as they have done since the onset of the pandemic, but will still be held back by the overall weakness of global demand. These output prospects would allow only gradual declines in unemployment, and damp near-term incentives for companies to invest. Persistent slack would also temper increases in wage and price inflation.

The outlook would be brighter if faster progress towards developing and distributing an effective vaccine reduces uncertainty and the need for precautionary saving. This would point the way towards a stronger recovery, especially in 2022, and a more sustained pick-up in investment and consumer spending. On the downside, growth would be weaker if virus outbreaks were to intensify more widely, as is already the case in Europe, or if the challenges in ensuring widespread deployment of a vaccine proved to be greater than currently expected. This would imply an extended period in which containment measures were deployed to control the spread of the virus, and weaken growth prospects substantially. Confidence is still fragile, and further setbacks could remove any GDP growth in large parts of the world through 2021 or longer, deepening the already inflicted scars from the crisis.

Policies can play a pivotal role in supporting the economy while the health crisis persists and in easing the adjustment to a post-COVID-19 environment and governments need to react further if the recovery falters. Effective and well-resourced healthcare policies, as well as supportive and flexible macroeconomic and structural measures, are essential both to contain the impact of the virus and to minimise the potential long-run costs of the pandemic on living standards.

The current accommodative monetary policy stance needs to be continued, as planned, by key central banks in the advanced economies. Central banks should also continue to provide a backstop to credit markets, and ensure that low and stable interest rates are maintained. If economic weakness deepens, or appears likely to persist for longer than expected, the remaining limited scope to ease monetary conditions should be used.

Fiscal policy support needs to be pursued as long as containment measures limit economic activity, and also subsequently to help restore sustainable economic growth. Additional fiscal measures are required in some countries to avoid an imminent fiscal cliff when time-limited emergency measures expire. The aim for all countries should be to avoid a premature and abrupt removal of stimulus whilst economies are still fragile and growth remains hampered by containment measures. Public debt is set to rise substantially, from already high pre-crisis levels in some countries, requiring spending to be targeted effectively. Ensuring debt sustainability will be a priority only once the recovery is well advanced, although planning for the steps that may be needed should start now.

Exceptional crisis-related policies need to be increasingly focused on supporting viable companies, and accompanied by structural reforms that help to raise opportunities for displaced workers and vulnerable people, strengthen economic dynamism and mitigate climate change. Together, these can help to foster the reallocation of labour and capital resources towards sectors and activities with sustainable growth potential, raising living standards for everyone.

Many emerging-market economies and developing countries have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic. In some cases, extensive borrowing abroad to cushion the blow has added to existing challenges from high sovereign or corporate debt prior to the crisis. Debt restructuring for some of these borrowers is likely in the coming years. This process would be facilitated by increased transparency about the full extent of indebtedness, including contingent liabilities, and a more developed framework on how to deal with sovereign bankruptcy that includes all major creditors.

Stronger international co-operation remains necessary to help end the pandemic more quickly, speed up the global economic recovery, and build on the G20 efforts to address debt problems of emerging-market economies and developing countries. The sharing of knowledge, medical and financial resources, and reductions in harmful bans to trade, especially in healthcare products, are essential to address the challenges brought by the pandemic. International co-operation to ensure that a vaccine is available for everyone is necessary to ensure a faster rebound in global activity from the effects of the pandemic. Such preparation should also start now.

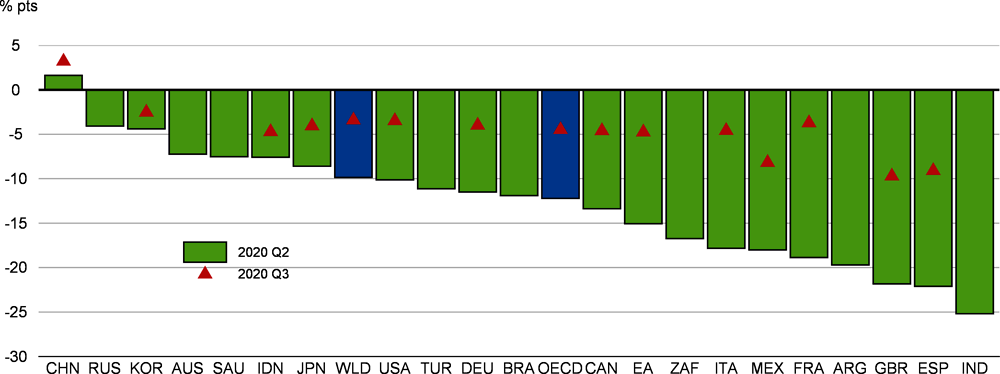

The economic outlook remains very uncertain, with the recovery in activity becoming increasingly hesitant. After the unprecedented sudden shock in the first half of the year, with global GDP in the second quarter of 2020 10% lower than at the end of 2019, output picked up sharply in the third quarter as containment measures became less stringent, businesses reopened and household spending resumed (Figure 1.1). Despite the welcome upturn, output in the advanced economies remained around 4½ per cent below pre-pandemic levels in the third quarter, close to the peak decline in output experienced during the global financial crisis. Without the prompt and effective policy support introduced in all economies to cushion the impact of the shock on household incomes and companies, output and employment would have been substantially weaker.

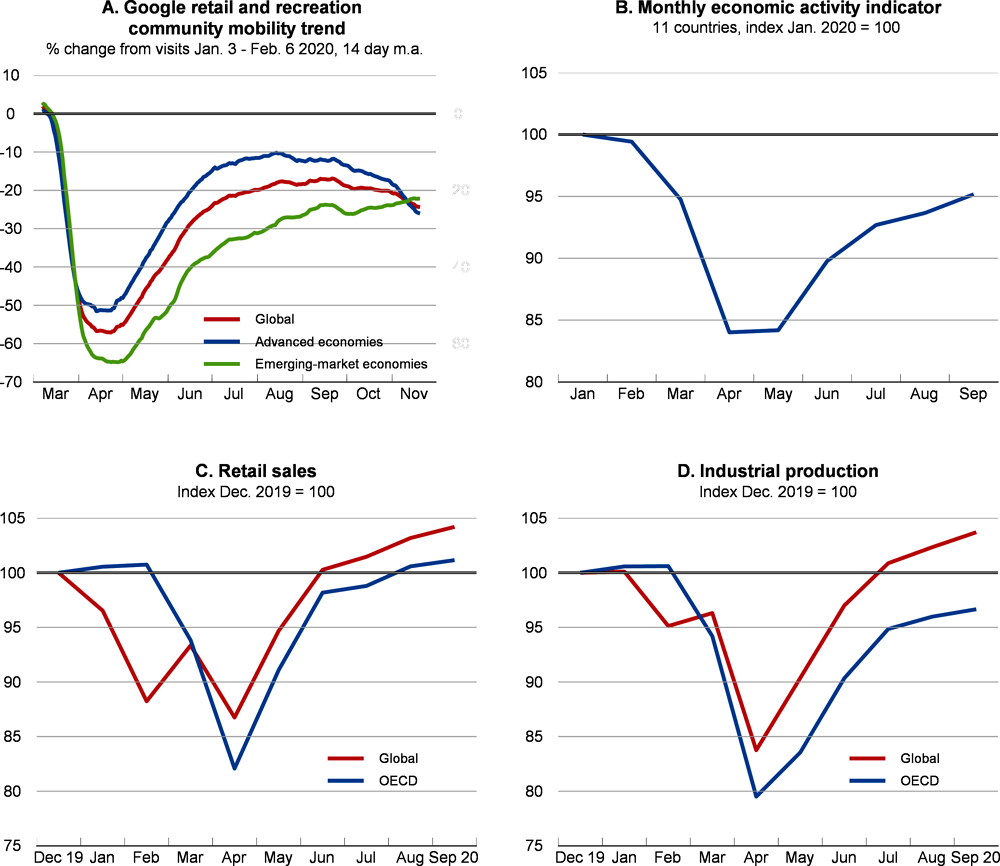

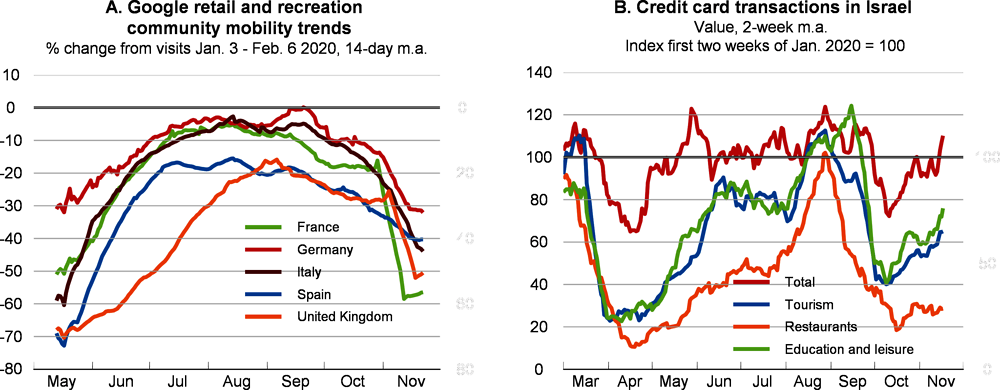

After the initial bounce-back in many activities following the easing of confinement measures, the pace of the recovery has eased recently, especially in Europe where output may now be declining again. Daily measures of mobility remain below pre-pandemic levels, and have begun to turn down again in the advanced economies (Figure 1.3, Panel A), with more stringent containment measures being implemented to address renewed virus surges. Search-based Google Trends indicators up to mid-November also suggest that GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2020 may be negative in many European countries where the stringency of containment measures has been tightened recently (Chapter 2, Issue Note 1). As seen in the second quarter of 2020, more stringent containment measures, and lower mobility are associated with weaker activity outcomes (Box 1.1). The initial rebound in some business surveys has also weakened, particularly in services. Amongst the countries with monthly economy-wide estimates of economic activity, just over two-thirds of the decline in output between January and April had been restored by September (Figure 1.3, Panel B), but with marked differences across sectors (Box 1.2).

Some categories of spending bounced back relatively quickly as economies reopened, particularly household retail spending (Figure 1.3, Panel C). Household spending on services, especially ones requiring close proximity between producers and customers or international travel, remains more subdued. In the United States and Japan, two economies with monthly estimates of total consumers’ expenditure, aggregate spending remains around 4% below immediate pre-pandemic levels.

Household saving rates rose by between 10 to 20 percentage points in most advanced economies in the second quarter, with government emergency measures supporting incomes, higher precautionary saving, and restrictions on consumer spending. Household bank deposit holdings also soared in many economies (Box 1.3). While this provides scope to finance additional spending, survey evidence suggests that precautionary saving could remain elevated while confidence is subdued and uncertainty persists about the evolution of the virus and labour market developments (Bank of Canada, 2020).

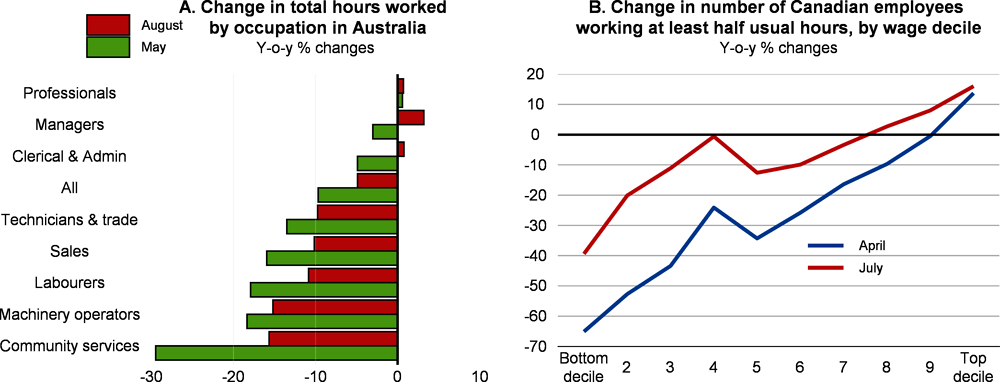

A significant proportion of the additional saving has accrued to higher-income households with a lower marginal propensity to consume (Bounie et al., 2020; Chetty et al., 2020), reflecting the extent to which the pandemic has added to existing income inequalities. Reductions in hours worked during the pandemic have been concentrated amongst lower-skilled occupations and lower-paid workers (see below). Containment measures may have also constrained the spending of higher-income households to a greater extent, reflecting a relatively high share of spending on service activities such as international travel, dining-out and cultural events.

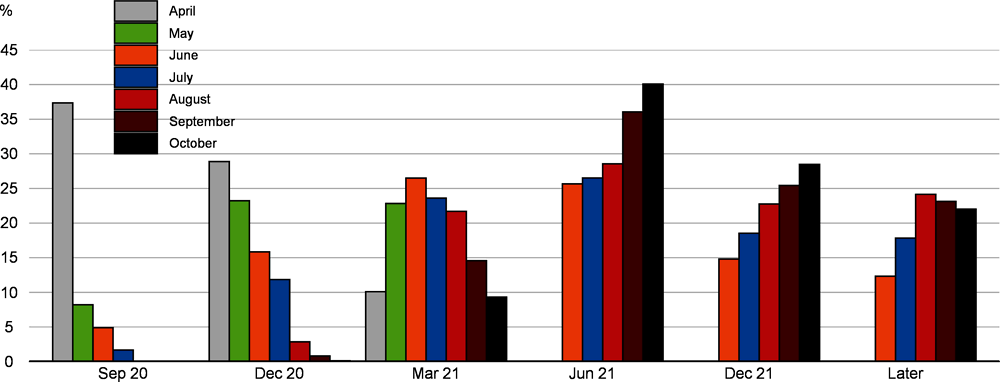

Global industrial production has also recovered, helped by strong growth in China (Figure 1.3, Panel D). However, shortfalls from pre-pandemic levels remain in many advanced economies, with demand for specialised capital goods being much weaker than for consumer goods, particularly in Japan and Germany. Investment intentions have weakened in several countries, and expectations that virus-related uncertainty will persist for some time (Figure 1.6) will keep business investment at low levels.

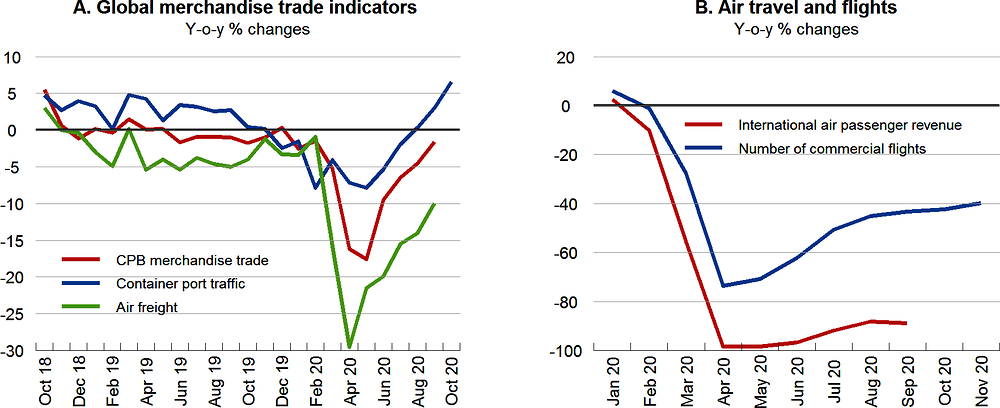

Global trade volumes contracted sharply in the first half of 2020, with merchandise trade falling by 16% from its pre-pandemic level, and international travel and tourism being largely curtailed (Figure 1.7, Panel A). The pick-up in activity during reopening has been reflected in trade and container port traffic, especially in China, Korea and a number of smaller Asian economies such as Vietnam, helped by the rise in global demand for masks and other personal protective equipment, and teleworking-related goods, including IT equipment. The recovery in industrial production in China has also boosted demand for many raw materials in commodity exporting economies, particularly metals. Survey measures of global export orders have recovered from their trough in April, but remain soft. Air passenger traffic and travel also remain exceptionally weak (Figure 1.7, Panel B), hitting export revenues in tourism-dependent economies.

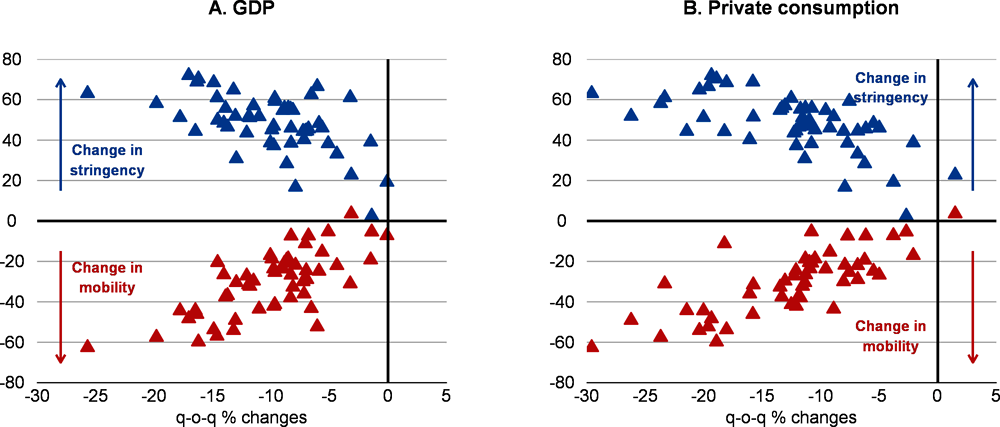

In the second quarter of 2020, output and consumer spending declined sharply in many advanced and emerging-market economies (Figure 1.2). However, the extent of the contraction differed significantly across countries, with GDP and private consumption falling by over 15% in some countries, and by 5% or less in others. This box highlights the strong cross-country association between activity, the strictness of containment measures and changes in mobility, complementing the detailed analysis of the relationship between mobility and containment policy measures (Chapter 2, Issue Note 4).

Containment measures are captured using the aggregate stringency index produced by the Oxford Blavatnik School of Government (Hale et al., 2020), and mobility by the Google indicator of retail and recreational mobility. Changes in containment measures are associated with changes in mobility, but mobility measures may also pick up other factors, such as voluntary physical distancing, or a reluctance to leave the home when concerns about the pandemic are high.

Empirical investigation

Both mobility and the stringency of containment measures are strongly correlated across countries with GDP growth and private consumption growth (Figure 1.2). The relative importance of these indicators can also be assessed econometrically using cross-country equations for quarterly changes in real GDP and private consumption in the second quarter of 2020. Two separate equations are estimated to allow for the possibility of differences in the extent to which mobility and stringency affect different activity indicators. For instance, cross-country variation in GDP growth stems in part from factors that may be less directly affected by domestic containment measures, such as government consumption and exports.1 Both explanatory variables are expressed as the change in quarterly average values.2 The equations are estimated for a group of advanced and emerging-market economies for which data are available, and exclude large outliers (leaving a sample of 43 economies for private consumption and 49 for GDP).3

Both mobility and stringency are found to have been significantly associated with cross-country differences in growth outcomes in the second quarter of 2020.

The results imply that a tightening of the average Oxford stringency index by 10 points is associated with a reduction of around 1 percentage point in quarterly GDP growth, for a given level of mobility, with a decline of 10 points in the Google community mobility indicator associated with a reduction of around 1.7 percentage points in quarterly GDP growth. For real private consumption growth, the respective numbers are 0.6 and 2.8 percentage points. The larger impact of the mobility indicator on consumption growth than on GDP growth may reflect the fact that retail and recreational mobility is more relevant for household consumption than for other economic activities.

The estimated equations explain roughly 60% of the cross-country variation in GDP growth and around 75% of the cross-country variation in private consumption growth.

For both GDP and private consumption equations, the residuals tend to be on average positive in Asia, where containment measures have been relatively mild in some countries, but negative in Europe, where more-restrictive measures were applied. This may point to some potential non-linearities in the aggregate relationships between growth, mobility and containment measures, or it may indicate that some particular types of containment measures, such as full shutdowns, have stronger effects than others.

It is too early to know whether the cross-sectional relationships found for the second quarter of 2020 can be used to help track output growth through the pandemic. However, early flash estimates for GDP growth in the third quarter of 2020 have continued to be correlated with quarter-on-quarter changes in mobility across countries. The estimated relationships for the second quarter of 2020 also provide a guide for potential developments in the fourth quarter of 2020, suggesting that growth may again turn negative in countries that are tightening confinement measures substantially and experiencing marked declines in mobility indicators. However, the relation may be slightly weaker as some sectors have not reopened, or their activity remains subdued. There may also have been a growing shift to on-line sales of goods and services.

← 1. International comparison is further complicated by different statistical approaches to measuring output volumes of the public sector during lockdowns (see fiscal policy section).

← 2. In both equations, the two indicators are significant at least at a 2% significance level. The significance is robust to exclusion of the country outliers.

← 3. The group covers most OECD economies and several non-OECD economies from Asia, Latin America and Africa. The sample for private consumption is smaller given fewer emerging-market economies with quarterly data for private consumption.

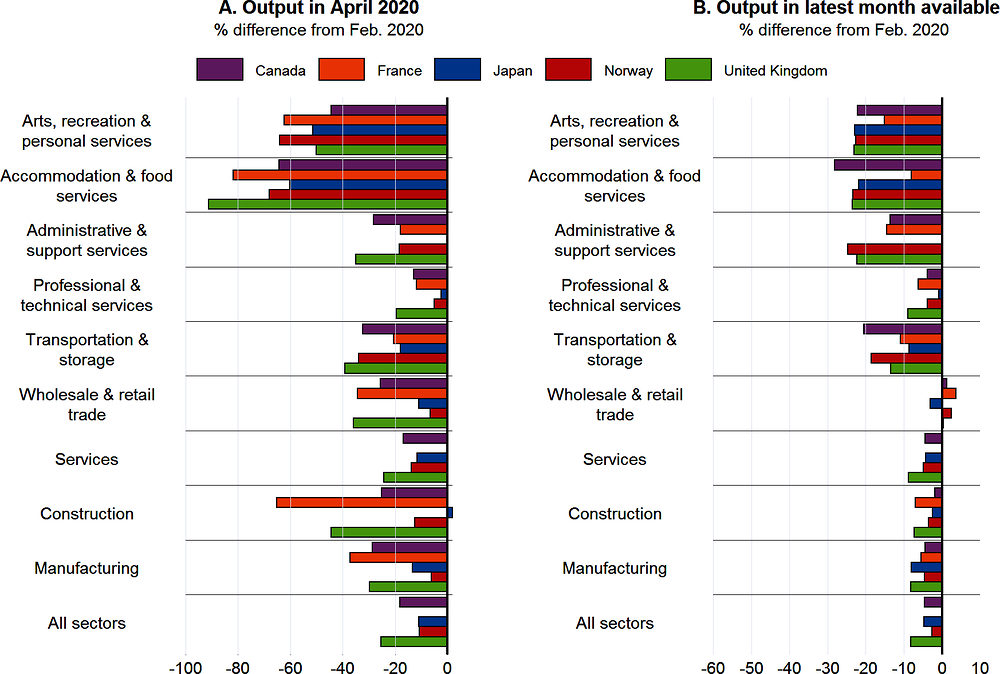

As anticipated at the start of the pandemic, the economic impact has varied across sectors. Monthly output data and special business surveys being undertaken in some countries provide a timely indication of the different impact of the pandemic across businesses, both in the early stages of the crisis and subsequently. Differences across countries in the containment measures used in response to the pandemic, and changes in consumer behaviour, often beginning before containment measures took effect, have both had a significant impact on activity, particularly in service sectors.

The initial decline in output was especially marked in countries such as the United Kingdom and France, where full economy-wide confinement was required for an extended period (Figure 1.4, Panel A). In contrast, other countries, particularly in Asia, used regional or sector-specific containment measures, and relied more extensively on an effective test, trace and isolate system to control the virus.

In the first two-three months of the pandemic, output fell particularly sharply in service activities requiring close proximity between consumers and producers, or large crowds, or travel (Figure 1.4, Panel A), declining by 60-80% in several countries.

Output in many other parts of the economy, including manufacturing, construction and most other market-based services also tumbled, although the extent of the decline was more varied, possibly reflecting the mix of containment measures being imposed and differences in specialisation. Declines in these sectors were typically somewhat larger in Canada, France and the United Kingdom than in Japan or Norway.

As the recovery has progressed, with many containment measures relaxed until recently, output has gradually picked up in most sectors (Figure 1.4, Panel B).

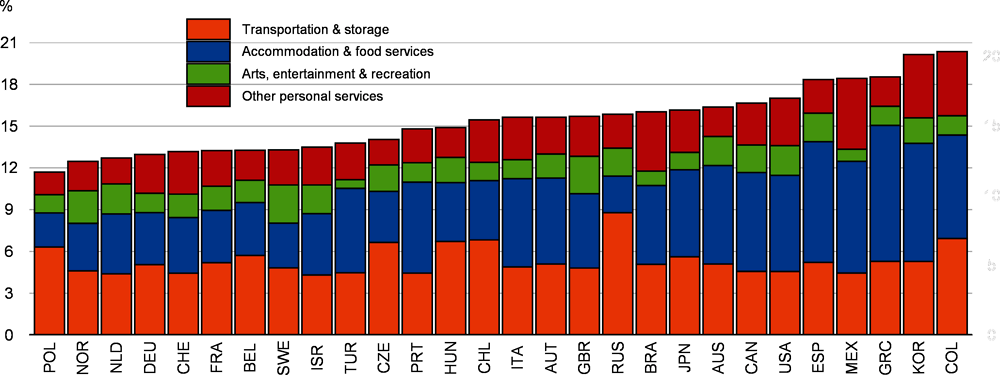

Output in the service sectors most affected initially has remained weak, raising the likelihood of persistent costs from the pandemic. Activity in accommodation, food services, events and recreation, and transportation, particularly air travel services, all continue to be impacted by physical distancing requirements and border closures.

The recovery has also been slow in administrative and support services, a category of output that includes travel agencies, where demand is extremely weak. Professional and technical services activity has been less affected, but the rebound since April has also been muted, likely reflecting general demand weakness.

In contrast, wholesale and retail trade output has largely returned to the immediate pre-pandemic level, helped by the strong rebound in retail sales.

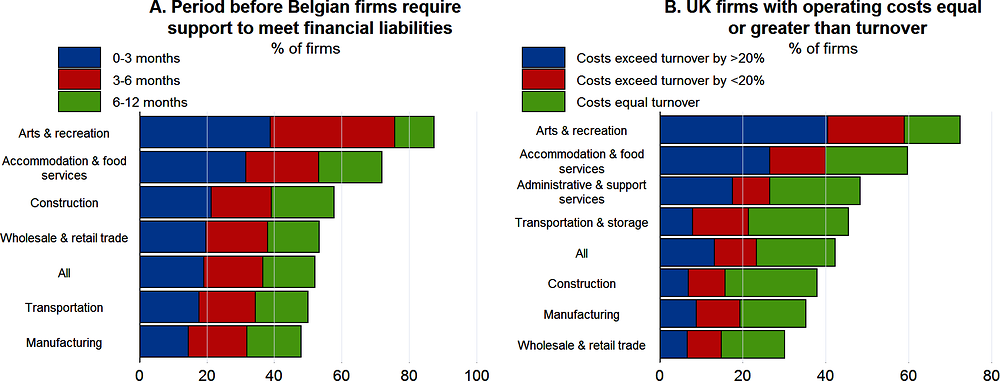

The special business surveys being undertaken by some national statistics offices and central banks provide additional insight into the effects of the pandemic across sectors, including on workforce arrangements, the extent to which government support schemes are being used, investment plans, and corporate finances (OECD, 2020a). A common pattern across countries for which data are available is the extent to which future investment plans have been revised down in all sectors.

Information on financial status and operating costs highlights the pressures that some firms continue to face, especially in the hardest-hit service sectors.

In Belgium, around one-fifth of responding firms indicated that they could not meet their financial liabilities for more than three months without receiving additional equity or credit (Figure 1.5, Panel A). An additional sizeable share of firms indicated that financial liabilities could only be met for between three and six months.

Financial pressures are strongest in the events and recreation sector, and the accommodation and food services sector, with around 40% and 30% of firms respectively indicating that financial labilities cannot be met for more than three months.

In the United Kingdom, around one-fifth of responding firms reported that their operating costs were currently exceeding turnover, with the excess being over 50% in half of these cases (Figure 1.5, Panel B). A further one-fifth indicated that operating costs were equal to turnover.

Financial fragilities again appear to be greater in the hardest hit sectors. Around three-fifths of firms in the arts, recreation and entertainment sector, and two-fifths of firms in accommodation and food services, reported that operating costs currently exceeded turnover.

Answers to separate questions on perceived bankruptcy risk provide a similar picture for businesses who continue to trade. For instance, in the United Kingdom, around 18% of all firms report moderate or severe bankruptcy risks at the end of September; in accommodation and food services, the share was 38%.

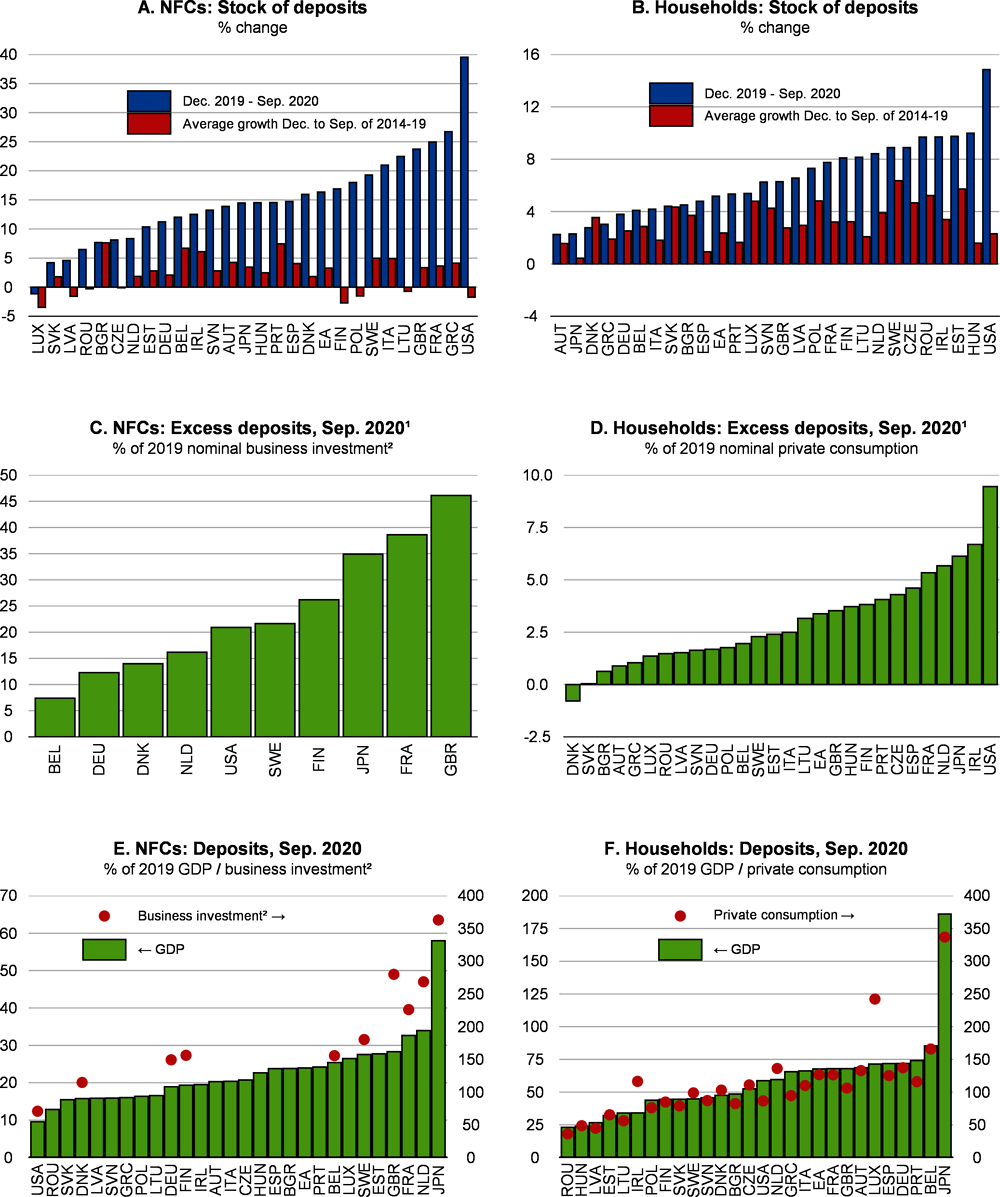

Unprecedented increase in bank deposits

Since end-2019, the bank deposits of non-financial corporations (NFCs) have increased rapidly in Japan, the United States and many European countries,1 far above the average growth rates over the same period in the past five years (Figure 1.8, Panel A). In contrast, in the global financial crisis, corporate deposits declined amid the credit crunch and, in some cases, a delayed policy response.2 Deposits of households have also increased but to a smaller extent; though still, in many countries, at a faster rate than in the previous years or at the beginning of the global financial crisis (Figure 1.8, Panel B).

Possible explanations

Several factors could explain the observed surge in deposits:

Containment measures made some household purchases impossible (Boxes 1.1 and 1.2) at a time when incomes were maintained by government support, thus increasing saving and bank deposits. This effect should be temporary and dissipate as containment measures are lifted gradually and pent-up demand is satisfied. Indeed, so far, growth in deposits was concentrated in the March-May period, when strict lockdown was in force in many countries. In the following months, until the recent reintroduction of containment measures, the rate of growth in deposits of both households and NFCs slowed in most countries, though it remained above the average rate over the same period in the past five years.

Containment measures are likely to have particularly affected consumption of some high-ticket services by high-income households, stimulating aggregate savings. High-income households tend to spend a higher share of their income on services that are heavily affected by containment measures, such as international travel, restaurants and cultural events. As the restrictions are likely to persist, so does this motive for saving.

High uncertainty about the pandemic and future economic prospects has strengthened motives for precautionary saving, discouraging investment and purchases of durable goods.3 These effects are likely to be more persistent.

Amid disruptions to revenues, NFCs’ preferences for holding cash have increased with the aim of raising their buffers and avoiding liquidity shortfalls. Cash hoarding was facilitated by drawing on loan facilities (e.g. revolving credit lines), issuance of corporate bonds by large firms (Goel and Serena, 2020), and by government sponsored loan programmes.4 NFCs could have also reduced riskier financial investments (e.g. in money market funds).

Crisis-related tax deferral measures have helped households and NFCs to increase liquidity and could have persistent effects, as money could be kept aside to meet postponed tax obligations. Tax deferrals are officially estimated to be high in some countries, exceeding, for example, 13% of GDP in Italy and close to 5% of GDP in Japan.

Possible implications

A reversal in any of the above factors may result in additional investment and consumption, boosting aggregate demand and accelerating the economic recovery. Back-of-the-envelope calculations show that “excess” deposits are large relative to pre-crisis business investment, potentially indicating a sizeable future impact on investment (Figure 1.8, Panel C). For households, “excess” deposits are relatively small relative to private consumption (Figure 1.8, Panel C), but both household deposits and consumption are much larger relative to GDP (Figure 1.8, Panels E and F), potentially implying a bigger aggregate impact.

However, there are several reasons why these excess savings may not boost aggregate private demand beyond negative confidence effects. For example, the distribution of deposits may be skewed. If the increase in NFCs’ deposits has been driven by a few large firms that benefitted from the crisis, particularly in the technology sector, excess deposits are unlikely to stimulate future economy-wide investment. Similarly, if the increase in household deposits were mostly driven by high-income households with a relative low marginal propensity to consume, then a reduction in uncertainty and containment measures would not necessarily lead to a broad-based strengthening of consumption. Moreover, firms could use excess deposits to settle payments due to other companies, creditors or tax authorities.

← 1. Country coverage is determined by the availability of data for non-financial corporations and households.

← 2. The growth rate of bank deposits is computed over nine months from the start of the global financial crisis (2008Q4 for European countries and Japan, and 2008Q3 for the United States) to ensure comparability with the data available for the COVID-19 crisis.

← 3. For example, Mody et al. (2012) show that the change in the unemployment rate – a proxy for variation in economic uncertainty – boosts precautionary savings.

← 4. In November, the size of the resources made available to the economy through government-sponsored loan programmes (loans and guarantees) was above 10% of 2019 GDP in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain and the United Kingdom.

High-frequency data suggest that the recent resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the containment measures implemented in response, are again weakening activity and mobility in affected countries, particularly in Europe. Most governments initially resorted to targeted localised restrictions on specific regions or activities, but these have not sufficiently checked the upturn in new COVID-19 cases, especially in countries that lack an effective track, trace and isolate system and in which compliance with quarantine restrictions is patchy. New cases were initially concentrated amongst younger people, but hospitalisations are now also rising sharply, as older people catch the virus. As a result, some governments have now imposed significant nationwide restrictions once again, including the closure of many businesses. Mobility indicators related to retail and recreational activities have turned down since the start of September in the major European economies (Figure 1.9, Panel A), though to a smaller extent than seen last April. In Israel, where a second nationwide lockdown was implemented from mid-September to mid-October, credit card spending plummeted almost as sharply as in the first full lockdown (Figure 1.9, Panel B), especially on already hard-hit service activities, raising the risks of higher unemployment and bankruptcies. This indicates the extent to which renewed nationwide or widespread lockdowns could have powerful negative effects on activity, as in the first wave (Box 1.1).

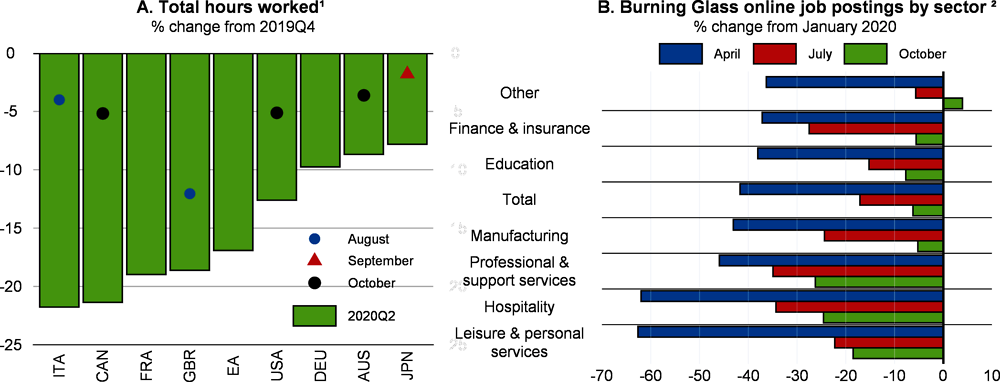

Additional containment measures are likely to place further pressure on labour markets. Hours worked fell sharply at the height of the pandemic and have recovered slowly since then (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Job prospects and hours worked continue to diverge across sectors, remaining especially weak in some of the service sectors most affected by containment measures and restrictions on international travel. The divergence in outcomes across sectors has also been reflected in differences in labour demand by types of occupation and by earnings levels (Figure 1.11). Total hours worked have fallen particularly sharply for lower-skilled workers and for workers at the bottom end of the earnings distribution in many countries, adding to the high level of inequality that existed prior to the pandemic.

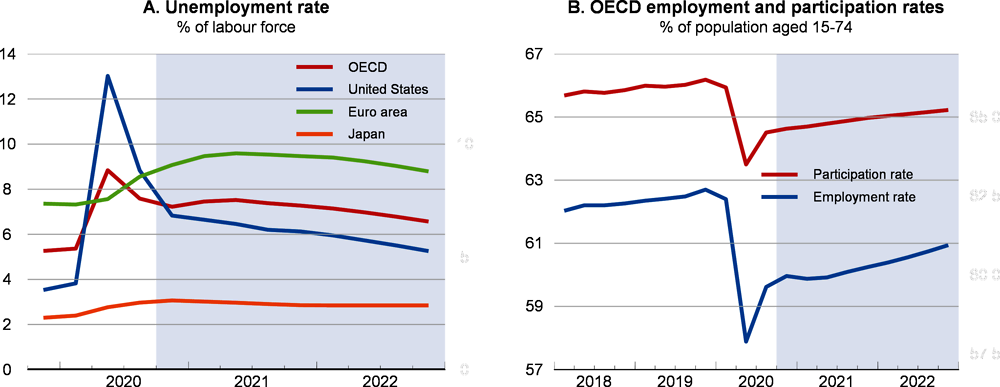

In the median OECD economy, the unemployment rate in September was around 1¼ percentage points higher than immediately prior to the pandemic, but this masked considerable differences across economies. Unemployment has edged up only mildly in Japan and in many European economies, largely due to job retention measures such as short-time work and wage subsidies, but has risen sharply in the United States and Canada, as well as in some emerging-market economies hard hit by the pandemic.1 Younger people have been especially affected, with the youth unemployment rate rising by over 3 percentage points in the median OECD economy since February this year. High-frequency indicators of hiring rates and new job postings have begun to recover after falling sharply at the height of the pandemic, particularly in services (Figure 1.10, Panel B).

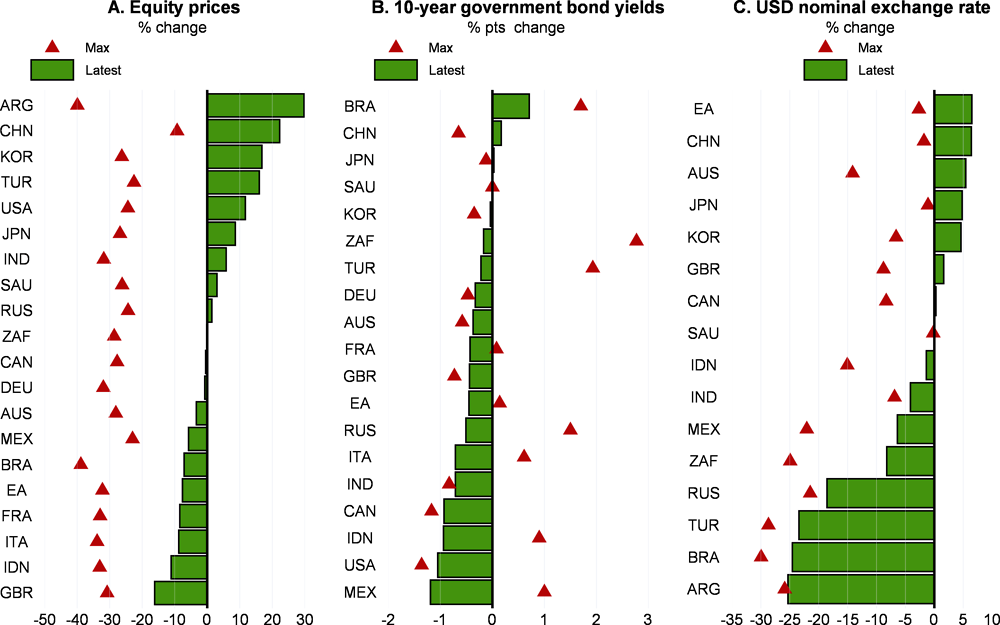

In spite of a highly uncertain outlook, financial conditions have largely normalised since the peak of the crisis following rapid and sweeping responses by central banks. The fast spread of the pandemic and strict containment measures triggered historical declines in financial asset prices and a general spike in volatility in March and April, with some markets ceasing to function properly. Since then, equity prices have rebounded across the board, and volatility indicators have reverted to historical standards, despite their recent fluctuations in some economic areas (Figure 1.12, Panel A). Long-term government bond yields have remained low in many advanced economies, after having reached historical lows amid the massive monetary policy easing, a general flight to safety and the subdued outlook (Figure 1.12, Panel B). With a few exceptions, currencies have also bounced back against the US dollar in key advanced and emerging-market economies, reflecting both improving global risk sentiment and concerns about a worsening of the COVID-19 crisis in the United States.

Importantly, financial stability concerns have abated in the more fragile segments of the market. Capital flows to emerging-market economies have quickly rebounded after the March sell-off, alleviating the funding pressures faced by many sovereign borrowers with massive fiscal needs. Tensions have also eased in the corporate sector in both advanced and emerging-market economies, with large firms successfully tapping markets to raise cash and/or build buffers, and corporate bond spreads reverting to their pre-crisis level for investment-grade borrowers. However, a number of lower-rated corporate and sovereign borrowers still face high borrowing costs and/or have delayed new issuances.2 While downgrades of corporates – which have been concentrated amongst weaker debtors – have slowed and so far remained below the peaks during the global financial crisis, negative outlooks are at unprecedented highs (IMF, 2020; Standard and Poor’s, 2020). So far, banks in the main advanced economies have remained resilient thanks to robust capital and liquidity buffers (Bank of Japan, 2020; Lagarde, 2020a; Quarles, 2020). However, banks’ equity prices have remained significantly below pre-crisis levels, profitability has declined and lending standards have generally tightened, with banks continuing to suffer losses if economic activity in specific sectors remains subdued or contracts further. Money market funds and investment funds have also experienced significant liquidity stress.

Financial stability concerns are likely to re-emerge. Although immediate liquidity pressures have disappeared, the continued rapid debt build-up in the sovereign and non-financial sectors will lead to solvency concerns in a large number of economies (Chapter 2, Issue Note 2). For instance, speculative-grade corporate default rates in the United States and Europe are projected to double by mid-2021 on some estimates, with hard-hit sectors such as airlines, hotels and the auto industry likely to be particularly affected (Standard and Poor’s, 2020). Bankruptcies of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), especially in the hard-pressed accommodation, food and entertainment sectors, are also projected to increase (IMF, 2020; Box 1.2). In the United States, the high level of corporate debt and elevated valuations in commercial real estate prior to the crisis could also lead to higher-than-expected losses on loans to some of these businesses (Quarles, 2020).

Challenges might be particularly acute in some emerging-market economies, where policy options are more limited (see below) and there is greater exposure to global demand shocks. Countries relying extensively on the most severely affected sectors – such as tourism and hospitality – and commodity exporters are particularly affected. Although some commodity prices (such as food and metals) have recovered from their trough in April, helped by strong demand from China, the prices of other key exports remain subdued. The prospect of a rebound in tourism also remains very bleak in the short term, with consumers’ fears of contagion and international travel restrictions likely to persist well into 2021.

Moderate growth is set to continue provided the pandemic can be contained effectively

The near-term global outlook remains highly uncertain. Growth prospects depend on many factors, including the magnitude, duration and frequency of new COVID-19 outbreaks, the degree to which these can be effectively contained, the time until an effective vaccine can be widely deployed, and the extent to which significant fiscal and monetary policy actions continue to support demand. Recent developments point to a rising possibility that effective vaccines will be widely deployed towards the end of 2021, improving the prospects for a durable recovery. However, time will be needed to manufacture and distribute the vaccine around the world and ensure it reaches those most at risk. Until then, sporadic and potentially sizeable outbreaks of the virus are likely to continue, as currently being experienced in many Northern Hemisphere economies, necessitating continued containment measures and strategies that differ across countries. Targeted restrictions on mobility and activity will need to be used to address any new outbreaks, accompanied by reinforced personal hygiene measures. Limits on personal interactions are assumed to persist, such as physical distancing requirements and restrictions on the size of gatherings. Restrictions on people crossing national borders are also expected to remain in force, at least partially. Voluntary physical distancing may also continue to restrain household spending.

Living with the virus for at least another six to nine months is likely to prove challenging. The impact of renewed periods of tighter containment measures on activity and confidence will differ across economies, depending on the effectiveness of testing, contact tracing and quarantine arrangements, and the availability of sufficient hospital capacity. However, even where outbreaks are more easily controlled, some of the service sectors most affected by restrictions may be disrupted. With these sectors accounting for a sizeable share of total activity and employment in many economies, adverse spillovers from job losses and bankruptcies into demand in other parts of the economy are likely. Persistent unemployment would also worsen the risk of poverty and deprivation for millions of informal workers. Pre-existing vulnerabilities that have been heightened by the pandemic, such as high corporate and sovereign debt in many countries, and trade tensions between the major economies, could also slow the pace of the recovery if there are prolonged outbreaks of the virus.

Based on the assumptions set out above, a gradual but uneven recovery in the global economy is projected to continue in the next two years following a temporary interruption at the end of the current year. After a decline of 4¼ per cent in 2020, global GDP is projected to pick up by 4¼ per cent in 2021, and a further 3¾ per cent in 2022 (Table 1.1; Figure 1.13, Panel A). OECD GDP is projected to rise by around 3¼ per cent per annum in 2021 and 2022, after dropping by around 5½ per cent in 2020. By the end of 2021, the level of global output is projected to have returned to that at the end of 2019 (Figure 1.13, Panel C), although this is not the case in all countries.

Output is set to remain persistently weaker than projected prior to the pandemic (Figure 1.13, Panel D), suggesting that the risk of long-lasting costs from the pandemic is high. Such shortfalls are projected to be relatively low in China, Korea, Japan and some Northern European economies, at between 1-2 per cent in 2022. The median advanced and emerging-market economy could have lost the equivalent of 4 to 5 years of per capita real income growth by 2022. Initial estimates of potential output growth in the aftermath of the pandemic also highlight the likelihood of permanent costs from the outbreak, with potential output growth in the OECD economies projected to slow to just over 1¼ per cent per annum in 2021-22, some ½ percentage point weaker than immediately prior to the crisis.

Considerable heterogeneity in developments in the major economies is set to persist, both between advanced and emerging-market economies, and between regions (Figure 1.13, Panel B). The economic impact of the pandemic and its aftermath has been relatively well contained in many Asia-Pacific and Northern European economies, reflecting effective containment measures, including well-resourced test, track and isolate systems, and familiarity with precautionary measures to protect against risks from transmissible diseases. In contrast, the measures required to control virus outbreaks in other parts of Europe and other emerging-market economies have been prolonged and involved much deeper declines in output.

In the United States, GDP growth is projected to be between 3¼-3½ per cent over the next two years, after an output decline of 3¾ per cent in 2020. High uncertainty, elevated unemployment, and further localised virus outbreaks are likely to restrain the pace of the recovery, particularly in the near term, but an assumed additional fiscal package early in 2021 should help to support household incomes and spending, and accommodative monetary policy will continue to boost activity, particularly in the housing market.

A gradual recovery is underway in Japan, with GDP growth projected to be around 2¼ per cent in 2021 and 1½ per cent in 2022, following an output decline of 5¼ per cent in 2020. Improving external demand will help exports strengthen further, but weak real income growth is likely to hold back private consumption. Strong fiscal measures have helped to cushion activity this year but a tighter fiscal stance in 2021, despite the new supplementary budget announced in November, will slow the pace of the recovery.

In the euro area, GDP has declined by 7½ per cent this year, and near-term prospects are weak. Output is projected to drop by close to 3% in the fourth quarter of 2020, reflecting the recent reintroduction of stringent containment measures in most countries. Provided virus outbreaks can be effectively contained in the near term, and confidence restored, a moderate recovery is projected in 2021-22. However, area-wide pre-pandemic output levels may not be fully regained until after 2022. After sizeable support this year, fiscal policy is set to be broadly neutral in 2021 and mildly restrictive in 2022 despite the modest outlook, but Next Generation EU grants should help support investment in the hardest-hit economies during the projection period.

A solid recovery is expected to continue in China, with GDP growth projected to be around 8% in 2021 and 5% in 2022. Monetary stimulus is now being withdrawn but fiscal policy is set to remain supportive. Strong investment in real estate and infrastructure, helped by policy stimulus and stronger credit growth, and improved export performance are driving the pick-up, and helping to boost external demand in many commodity-producing economies and key supply-chain partners in Asia. Progress in rebalancing the economy has however slowed, and significant financial risks remain from shadow banking and elevated corporate sector debt.

The impact of the pandemic in many other emerging-market economies has been prolonged relative to that in China, reflecting difficulties in getting the pandemic under control, high poverty and informality levels, declining tourist inflows, and limited scope for policy support. Gradual recoveries are now starting in most economies, but the shortfalls from expectations prior to the pandemic are likely to remain sizeable.

Output in India is projected to rise by 8% in FY 2021-22 provided confidence improves, after having declined by 10% in FY 2020-21. Further reductions in policy interest rates should help to support demand, if the current upturn in inflation subsides, but there is limited scope for additional fiscal measures, and pressures on corporate balance sheets and banking sector bad loans are also likely to restrain the pace of the upturn.

A gradual recovery is projected to continue in Brazil, with GDP rising by 2½ per cent in 2021 and 2¼ per cent in 2022, after contracting by 6% this year. Strong fiscal and monetary support have helped to protect incomes and prevent a larger output decline this year. High unemployment and the planned withdrawal of some crisis-related fiscal measures will temper household spending in 2021, but historically low real interest rates and favourable credit conditions should help investment to strengthen.

Fiscal support is helping to underpin demand in the near term, with job retention schemes and business support measures continuing in many countries, but this is unlikely to be able to prevent rising business failures and attendant job losses in the service sectors most affected by ongoing containment measures until an effective vaccine is widely deployed. In the median OECD economy, using conventional but uncertain estimates of the fiscal stance based on changes in the underlying primary balance, a mild fiscal tightening of 0.7% of GDP is expected in 2021, after easing of 4.2% of GDP in 2020. The exceptional additional monetary and financial policy measures introduced since the start of the pandemic are important for economic stabilisation, helping to ensure financial stability and limit debt service burdens. However, their impact on consumer spending and business investment will depend on the extent to which confidence recovers and firms lower their hurdle rates for investment.

High uncertainty, subdued confidence and employment are likely to keep precautionary saving elevated for a while, although this should fade slowly during 2021-22. The increasing concentration of saving amongst higher-income households with a lower marginal propensity to consume, and likely declines in the incomes of lower-income households, will also check the rebound in consumer spending in some countries (Box 1.3). In the advanced economies, private consumption is projected to rise by 3½ per cent per annum in 2021-22 after declining by over 6% this year, with household saving rates remaining above pre-pandemic levels throughout the projection period.

Soft demand growth and considerable uncertainty are likely to hold back investment for an extended period, particularly by companies with high debt. In the major economies, business investment is projected to be around 1¾ per cent higher in 2021 than this year on average, but with the level remaining well below that prior to the pandemic. A stronger pick up is projected in 2022, with business investment rising by over 4%. The recovery in housing investment is projected to be a little quicker, helped by the sensitivity of demand to lower mortgage rates, rising by 4% in the advanced economies in 2021. In spite of the recovery in gross investment, net productive investment appears set to weaken further. An extended period of weak investment adds to the risks of low output growth becoming persistent, and contributes to the estimated moderation of potential output growth in the aftermath of the pandemic. In the median OECD economy, net productive investment (business plus government) is projected to average 3¼ per cent of GDP over 2020-22, down from 4½ per cent of GDP over 2015-19.

Labour market conditions are projected to remain subdued. The unemployment rate in the OECD economies is expected to moderate only by around ¾ percentage point over the next two years, from around 7¼ per cent in the fourth quarter of 2020 (Figure 1.14, Panel A). Employment growth is projected to be only modest, with temporary wage and employment support schemes due to fade out in some countries. Continued uncertainty for much of 2021 may also mean that many companies initially choose to meet improved demand by expanding hours worked per employee, rather than the overall size of their workforce, particularly if they are retaining staff with assistance from job retention schemes. Many discouraged workers and those experiencing longer spells of unemployment may leave the labour force, damping participation, and some older workers may decide to retire earlier than expected. Employment and participation rates are projected to remain below their pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1.14, Panel B), contributing to the longer-term costs of the pandemic. Persisting slack in labour markets is in turn likely to check the growth of wages and incomes.

World trade is projected to continue recovering slowly, rising on average by around 4¼ per cent per annum over 2021-22, after declining by 10¼ per cent in 2020. The weak recovery in investment – a trade-intensive component of demand – and the likelihood that containment measures will continue to weigh on international travel and tourism both contribute to the modest rebound in overall trade.3 The trade decline in 2020 is broadly similar to that seen during the global financial crisis, despite the much greater fall in activity during the pandemic. In part, this reflects the sharp fall in consumer demand in services where trade intensity is low.

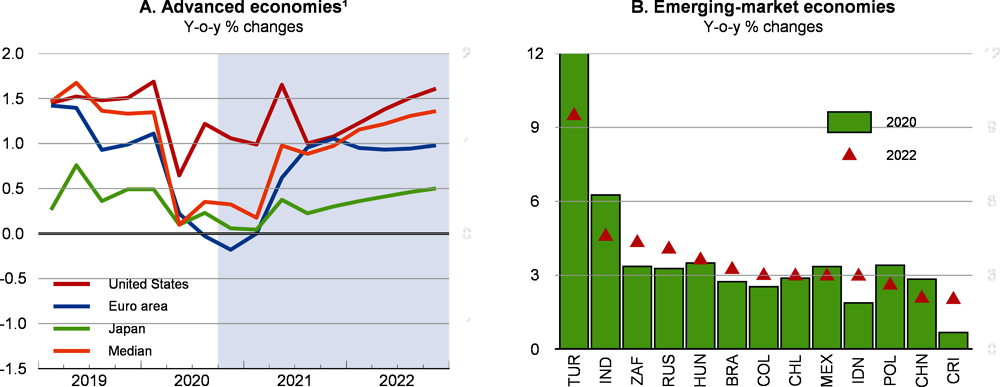

Inflation rates in advanced economies have rebounded since the trough in early/mid-2020, especially in the United States, but generally remain below pre-pandemic levels. This trend is projected to persist in the short term, with inflation being subdued in 2021 and converging slowly to pre-crisis levels only by the end of 2022 in most countries (Figure 1.15, Panel A). Inflation in most emerging-market economies is also expected to remain moderate, or even decline, over the next two years (Figure 1.15, Panel B). Although supply disruptions – such as non-tariff trade barriers or unexpected bottlenecks in global production and distribution – could accelerate the return to trend inflation, the forces currently weighing on aggregate demand around the world – contagion fears, high unemployment, and rising precautionary saving – clearly dominate the inflation outlook. As a result, inflation should remain well below central banks’ targets in the coming two years, especially in advanced economies. However, in emerging-market economies, inflation could be higher than projected if domestic currencies depreciate again.

A considerable amount of uncertainty still surrounds inflation dynamics. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many services have not been provided due to strict containment measures and many individual prices have had to be extrapolated by statistical offices (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020; Eurostat, 2020). This is expected to continue with the renewal of containment measures in some countries. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the way consumers allocate spending, potentially leading to an understatement of actual inflation (Cavallo, 2020). Available estimates of the changes in spending patterns caused by COVID-19 point to an increase in the weight of food at home in US consumption baskets, at the expense of transportation services, recreation and restaurants. Since food prices (transport prices) have generally risen (decreased) faster than other items, official inflation statistics based on pre-COVID-19 weights could understate the level of inflation faced by consumers. The inflation outlook also remains highly uncertain, given the special nature of the COVID-19 crisis, which affects both supply and demand and in very heterogeneous ways across individual items and countries. The balance of risks in the longer term, however, remains tilted to the downside given the influence of both cyclical and structural downward pressure on prices in most countries (Chapter 2, Issue Note 3).

Key risks to the projections

Uncertainty remains about the time before a vaccine can be widely deployed, and the impact it would have

The baseline projections are conditional on the evolution of the pandemic, the judgements about the actions taken to contain the spread of the virus and their economic impact, and the assumption that improving prospects for the successful deployment of a vaccine sustain consumer and business confidence. A wide range of outcomes could occur over the next two years. Two scenarios set out below use the NiGEM global macroeconomic model to illustrate the potential implications of alternative assumptions.

On the upside, a faster deployment than assumed of a vaccine could provide a greater boost to confidence and a stronger pick-up in spending than in the baseline projections. This would boost GDP growth, especially in 2022, and strengthen the impact of the monetary policy easing implemented since the start of the pandemic.

On the downside, if the challenges involved in producing and deploying an effective vaccine were to prove greater than expected, prolonging the period in which continued containment measures were required to limit COVID-19 outbreaks, confidence would remain weak for longer, and uncertainty deepen. This would further raise the risk of bankruptcies and job losses, particularly in sectors in which activity would be severely restricted again. Precautionary saving by consumers would increase, business investment would weaken, with capital being scrapped in some sectors, and substantial repricing could occur in financial markets, reflecting greater risk aversion. This would weaken global growth, particularly in 2021.

The upside scenario: a resurgence in confidence

The upside scenario considers the impact of a stronger boost to the confidence of consumers and companies, raising the prospects of a stronger rebound in spending and output. To illustrate this, an endogenous reduction in household saving rates is applied starting from the latter half of 2021 in all economies, with this shock fading slowly through 2022. Policy interest rates are assumed to remain at their baseline levels, implying an increasingly accommodative monetary policy stance as demand strengthens. The automatic fiscal stabilisers are allowed to operate fully in all countries, so that the fiscal balance improves as activity picks up.

Key features of the results are as follows:

Overall, the level of world GDP is raised by around 2½ per cent (relative to baseline) at the peak of the shock, with global GDP growth raised by ¾ percentage point in 2021 and 1¾ percentage point in 2022 (Figure 16, Panel A). This would bring global GDP growth to around 5% and 5½ per cent in 2021 and 2022 respectively.

Output returns to pre-pandemic levels more quickly in all regions (Figure 16, Panel B), and the gap between baseline activity and pre-crisis expectations is halved. World trade growth is also strengthened substantially, rising by around 3¾ percentage point (relative to baseline) in 2022, boosting exports in all economies.

The initial decline in the saving rate, higher household incomes as activity picks up and a 1 percentage point decline in the unemployment rate result in a substantial boost to spending, with private consumption over 3% higher in the advanced economies. Business investment is also stimulated by stronger demand, rising by 2¾ per cent (relative to baseline) in the median advanced economy. This boosts the capital stock and the prospects for a sustained recovery.

Stronger growth also helps to ease government debt burdens, with the government debt-to-GDP ratio declining by around 4 percentage points in the median advanced economy in 2022.

The downside scenario: heightened uncertainty and additional costs

The shocks considered in the downside scenario are as follows:

Consumer confidence is assumed to decline as prospects for an early deployment of the vaccine recede, reducing household spending and pushing up household saving rates by around 2 percentage points in the median advanced economy.

Heightened uncertainty and a longer period of weak demand are assumed to result in the further closure of businesses and the scrapping of capital through 2021. The shocks imply an ex-ante reduction of 1% in the business capital stock by the latter half of 2021, with additional reductions occurring endogenously as the collective impact of the shocks applied is felt on output and investment.4

Higher uncertainty and shortfalls in output developments relative to expectations are also assumed to result in weaker risk appetite and repricing in financial markets. This is captured by an increase of 50 basis points in the risk premia on corporate bonds and equities that persists throughout 2021, and declines of 15% and 10% respectively in global equity prices and non-food commodity prices.

All these shocks are assumed to fade gradually through 2022. Their impact is partly cushioned by policy responses. Monetary policy is allowed to be endogenous, with policy interest rates lowered (relative to baseline), but for illustrative purposes there is assumed to be a binding zero lower bound. Thus, policy interest rates either cannot become negative or remain unchanged where they are already negative. The automatic fiscal stabilisers are also allowed to operate fully in all countries, implying that governments do not react to the shock by attempting to maintain a previously announced budget path.

These shocks would have substantial adverse economic effects. Global activity could come to a virtual standstill through much of 2021 before recovering gradually through 2022, remaining well below the projected baseline path and further adding to the costs of the pandemic (Figure 1.16, Panel A). Global output would recover to pre-pandemic levels only at the end of 2022, a year later than in the baseline projection.

The level of world GDP is reduced by close to 4.5% (relative to baseline) at the peak of the shock, with the full-year impact lowering global GDP growth in 2021 and 2022 by 2¾ percentage points and 1½ percentage points respectively. Broadly similar effects occur in most major economies and regions in 2021, with Europe and North America hit more heavily than the Asia-Pacific economies (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Relatively strong output declines occur in small open economies with a high trade intensity, and in those countries where there are relatively few policy offsets, due to limited monetary policy space, or weak levels of social protection or automatic budgetary stabilisers.

Global trade is also affected significantly by the drop in demand, with trade growth declining by over 7 percentage points in 2021, relative to the baseline.

Higher household saving, greater uncertainty and tighter financial conditions result in substantial cutbacks in private demand and higher unemployment. Business investment declines by around 12% in the median advanced economy in 2021, and the unemployment rate rises by 1.7 percentage points by the end of the year.

The overall impact of lower commodity prices is broadly neutral. Commodity exporters are hit by lower export revenues, but commodity-importing economies benefit from lower prices.

The net effects of the combined shocks are deflationary, with consumer price inflation in the advanced economies pushed down by over 1¼ percentage point in 2021.

Reductions in policy interest rates in the economies that have policy space help to cushion the negative effects on domestic activity and provide support for an eventual recovery. Policy interest rates are lowered by 2 percentage points or more in several large emerging-market economies, and by 25 basis points in the United States and Canada.

In the median advanced economy, the government debt-to-GDP ratio is increased by over 7½ percentage points by 2022.

In the scenario set out above, all shocks are assumed to occur in all countries. It is possible that the direct impact of further and stronger COVID-19 outbreaks on consumer spending and investment could be limited in some countries, particularly those in the Asia-Pacific region with effective test, track and isolate schemes and strictly observed containment measures. Nonetheless, in an interconnected world, such economies remain fully exposed to external shocks, from weaker global demand, restrictions on cross-border travel, and fluctuations in global financial and commodity markets. Removing the domestic demand shocks in the major Asia-Pacific economies would lower the overall impact on global GDP by around one-quarter, but still leave global activity well below the baseline in 2021 and 2022.

Additional timely and well-targeted discretionary macroeconomic policy responses could also help to offset downside shocks, the resulting disruptions to the economy, and heightened financial market volatility. Fiscal actions may be needed, including prolonged support for indebted companies and continuations of job protection and income support schemes. Monetary and financial policy programmes will need to be scaled up or extended, particularly liquidity and lending support, and further steps taken to increase monetary policy accommodation. Options include expanded asset purchase programmes, or forward guidance to help interest rates stay low for longer. An expansion of government transfers by 2% of GDP for two years could offset around one-fifth of the overall shock, reducing the hit to global GDP growth (relative to baseline) by around 0.4 percentage point per annum on average in these two years. Effects from higher transfers might be stronger still if they could be targeted fully on low-income households with a high marginal propensity to consume.

The lingering risk that the downside scenario materialises is a particular concern, as a downside surprise (relative to the projections) would be more likely to induce repricing in financial markets and possible discontinuities from higher corporate bankruptcies. Monetary policy may also face increasing constraints in reacting to such a shock, particularly in countries in which policy rates are close to an effective lower bound.

The outlook for trade remains uncertain

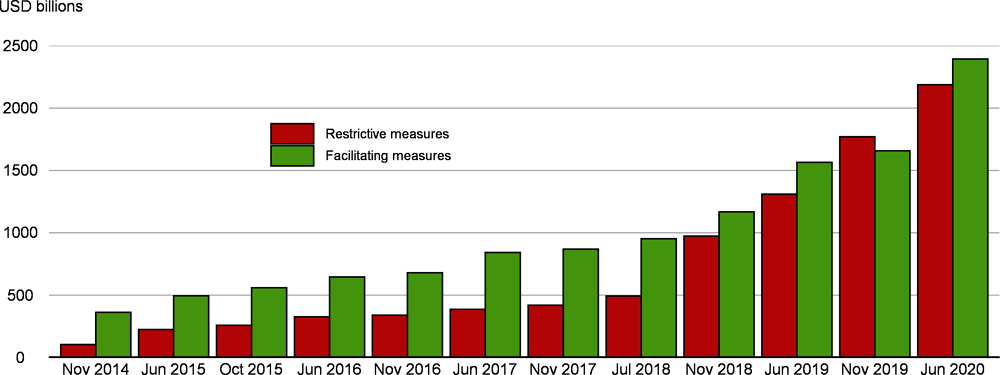

Many longstanding downside risks are still affecting the global trade outlook. However, the US-China Phase I agreement5 signed early this year, recent free trade agreements between the EU and some Asian partners and Mercosur,6 and a recent noticeable increase in trade-facilitating measures (Figure 1.17) show that some progress has been made in easing restraints on international trade. This has been further demonstrated by the trade pact recently agreed between members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) - China, Japan, Korea, Australia, the ASEAN countries and New Zealand - which reduces tariffs on trade for goods, expands market access for some services and unifies rules of origin within the block. Even so, some of the distortionary barriers to trade introduced around the world over the past two years are still in place. Tariff and non-tariff barriers remain high, and continue to limit global trade.

Uncertainty surrounding Brexit is also continuing to weigh on growth prospects. The transitional period agreed in the UK–EU Withdrawal Agreement will expire on 31 December 2020. If a deal is not ratified, the United Kingdom could end the transition period without any trade agreement, with particularly high risks of rising trade barriers, reduced labour mobility and lower foreign direct investment. Recent scenario analyses suggest that a no-deal exit of the United Kingdom from the EU Single Market would hit activity in the near term and continue to have strong negative effects in the medium term. It would entail physical and financial disruptions of different magnitudes across sectors, with exports falling by more than 30% in a few manufacturing sectors (notably the motor vehicle and transport, meat and textile sectors) and by almost 20% in the financial and insurance sector (OECD, 2020b).

A further source of uncertainty at the global level is that the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body has ceased to function while waiting for the appointment of a new members’ board, fuelling concerns about the capacity to fulfil its mandate of settling trade disputes and enforcing international rules.7

On top of this gloomy trade environment, the COVID-19 outbreak is creating additional downside risks. Many countries reacted in the early phase of the pandemic by tightening trade restrictions (for example on medical supplies) – particularly in Europe and North America. Even though many of these restrictions proved temporary, and were lifted quickly, they added to growing uncertainty. In the event of a substantial weakening in the recovery, with a new surge in global demand for medical supplies, a risk is that such restrictions could be reintroduced.

In addition, disruptions and shortages for a few but essential products have revived discussions about the costs of the international fragmentation of production. Reductions in trade dependency, including repatriating production, are seen as a potential way of reducing risk, but could also impose substantial efficiency costs. Besides, attempts to relocate production can weaken diversification, which reduces the scope for adjusting to shocks. Instead, since trade plays an important stabilising role, governments can strengthen resilience for most goods and services by taking actions to facilitate free movement. For some goods considered as “essential”, policymakers can also improve risk preparedness by monitoring the concentration of supply sources and increasing stockpiles.

With the virus continuing to spread in many regions of the world, and many countries experiencing a resurgence of cases, well-targeted public health measures and supportive macroeconomic and structural policies are required to preserve confidence and reduce uncertainty until an effective vaccine can be widely deployed. Governments need to use containment measures that control the virus without unduly burdening the economy (Chapter 2, Issue Note 4). Faced with the challenge of fostering the recovery while containment measures remain in place and some sectors undergo structural transformations, crisis-related support policies should be flexible and state-contingent, evolving as the recovery progresses to support workers and ensure assistance is focused on viable companies. Exceptional crisis-related policies need to be accompanied by the structural reforms most likely to raise opportunities for displaced workers and improve economic dynamism, fostering the reallocation of labour and capital resources towards sectors and activities that strengthen growth, enhance resilience and contribute to environmental sustainability. National policy efforts need to be accompanied by enhanced global co-operation to help mitigate and supress the virus, speed up the economic recovery, and keep trade and investment flowing freely.

Comprehensive public health interventions remain necessary

Comprehensive public health interventions remain necessary to limit and mitigate new COVID-19 outbreaks until vaccination becomes widespread. A key requirement is that healthcare systems can deal effectively with any resurgence of infections without unduly delaying necessary interventions for other patients. Governments need to maintain sufficient resources to allow large-scale test, track, trace and isolate programmes to operate effectively and limit further sharp rises in infection numbers, as has been achieved in several Asia-Pacific countries, and ensure adequate healthcare capacity and stocks of personal protective equipment. Mitigation measures, such as physical distancing and the widespread use of masks, also help to limit the spread of the virus (Chapter 2, Issue Note 4). Such steps would allow timely and targeted localised measures to be used to deal with new outbreaks, rather than renewed economy-wide confinement measures, limiting the overall economic and social costs. Nonetheless, new restrictions may still sap confidence and slow the pace of the economic recovery until a vaccine is deployed successfully.

Global co-operation and co-ordination remain essential to tackle the global health challenge. No country is able to obtain the range of products necessary to combat COVID-19 purely from domestic resources. Greater funding and multilateral efforts are needed to ensure efficient production of medical products and help affordable vaccines and treatments to be available swiftly everywhere. Decisions about stockpiling and health-emergency assistance in advanced economies should be designed in an inclusive way, taking into account the needs of the most vulnerable emerging-market economies and developing countries, where healthcare capacity is limited and resources are not available for significant investment.

Monetary policy needs to remain supportive

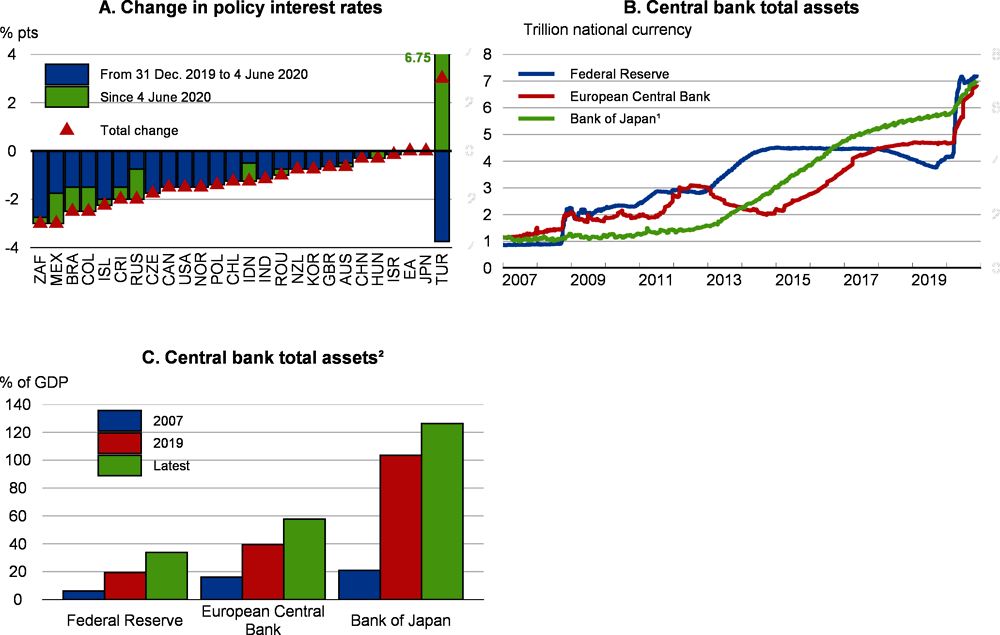

Advanced economies swiftly and markedly eased monetary and financial policies in response to the pandemic in the first half of the year. This involved interest rate cuts, renewed asset purchases, expansion of US dollar swap lines, and easing of bank prudential regulations (OECD, 2020c; Figure 1.18; Table 1.2). Since then, few new measures have been announced.8 This is warranted given some stabilisation in financial markets (see above) and the fact that many programmes are still being implemented. The main central banks continue to purchase government and private debt instruments, keeping interest rates low. Moreover, some announced liquidity and lending support measures have not yet been fully used (Table 1.3). The monetary authorities have committed to sustain credit support well until the crisis phase is over, and to act further if the outlook deteriorates, which is appropriate (Brainard, 2020; Kuroda, 2020; Lagarde, 2020b).

During the on-going crisis, giving strong support to demand, providing a backstop to key credit markets and ensuring financial stability should remain key objectives of monetary policy. The current numerous monetary and financial policy programmes offer flexibility to deal with sporadic virus outbreaks and associated disruptions to the economy and heightened financial market volatility. Buffers still exist within the current programmes, in particular regarding emergency lending and support to bank lending, which can be extended if needed (Table 1.3). While several programmes in the United States are about to expire by the end of 2020, they could be prolonged or reinstated.9 Also, asset purchases can be increased to ease general financial conditions. Any further easing of prudential regulation should be conditional on transparent disclosures of financial exposures and restrictions on dividend payments and bonuses.

If there are unexpected hurdles in deploying an effective vaccine, denting confidence and requiring further containment measures, with a renewed decline in economic activity, additional accommodation will be needed. While the scope to reduce policy rates in the main economic areas is limited,10 central banks have effective tools to maintain low government bond yields and thus pricing of credit in other segments of financial markets. The tools to control longer-term interest rates involve forward guidance on interest rates and larger net government bond purchases. To maintain low yields at longer maturities, central banks could also opt for yield curve control, similar to that pursued by the Bank of Japan.11 This framework helps to control the price of longer-term government bonds directly, in contrast to standard quantitative easing which focusses on the quantity of assets purchased.

In the longer term, the main challenge for monetary policy will be how to achieve sustainably higher inflation. Central banks already faced this challenge before the COVID-19 crisis, in the context of a secular decline in growth, inflation and estimates of the neutral interest rate. This has prompted reviews of the monetary policy frameworks by the main central banks (Chapter 2, Issue Note 3). In the United States, the review has resulted in the adoption of a flexible form of average inflation targeting, which is expected to help boost inflation. However, in advanced economies, a combination of structural changes over recent decades related to the production and distribution of goods and services, firms’ business models, and demand structure, may complicate the achieving of higher inflation, leading to a prolonged period of low interest rates. This would benefit fiscal sustainability (see below), but may result in excessive risk-taking in financial markets, in the absence of effective macro-prudential measures; reduced profitability of pension funds, insurance companies and banks; and perceptions that central banks contribute to rising inequality.

Fiscal policy support needs to be maintained in the short term

In many advanced economies, governments announced big support programmes at the beginning of the pandemic. Since then, the measures have been extended in some countries. While they vary in size and composition, the support to individuals and businesses has included primarily expanded short-time work schemes, extended unemployment benefits, extra sick and childcare leave, reductions in, or deferrals of, taxes and social security contributions, moratoria on private liabilities (such as rents, electricity bills and debt payments), loans, recapitalisations and loan guarantees. While not all of the budgeted allocations will be used (for instance, due to a low take-up) or reflected in budget balances according to national accounting conventions (for instance, some loan guarantees, tax deferrals and moratoria on private liabilities), fiscal support in 2020 is estimated to be massive in many OECD economies.12

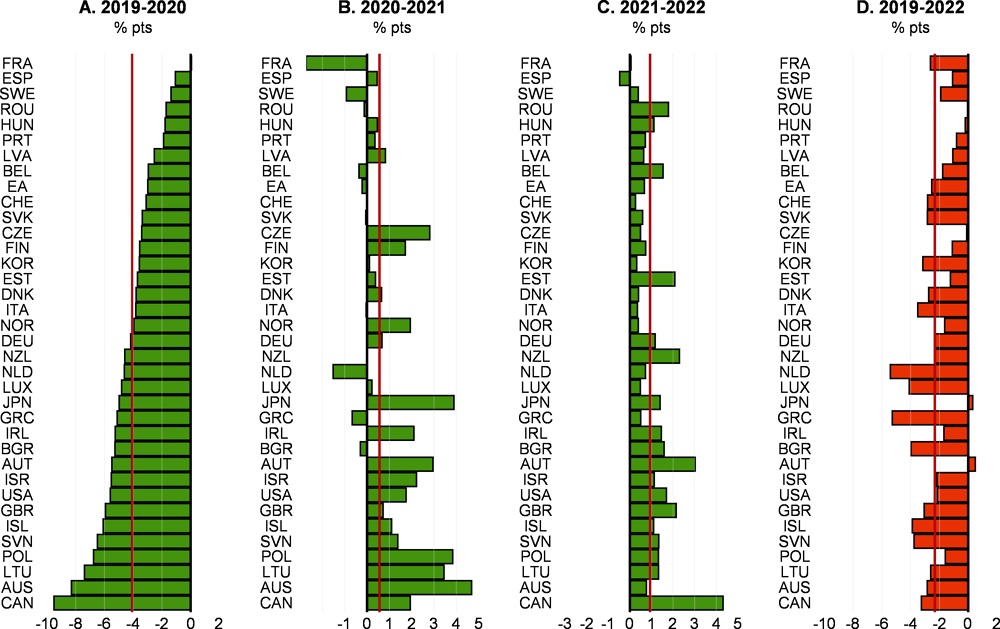

Discretionary fiscal easing, as approximated by the change in the underlying primary balance, is estimated to be 4.2% of potential GDP in the median OECD economy in 2020, but with considerable cross-country differences (Figure 1.19, Panel A). This is nearly twice as much as in 2008 and 2009. However, changes in estimated underlying primary balances should be treated with caution, as the standard cyclical adjustment framework may be less reliable in the current environment.13

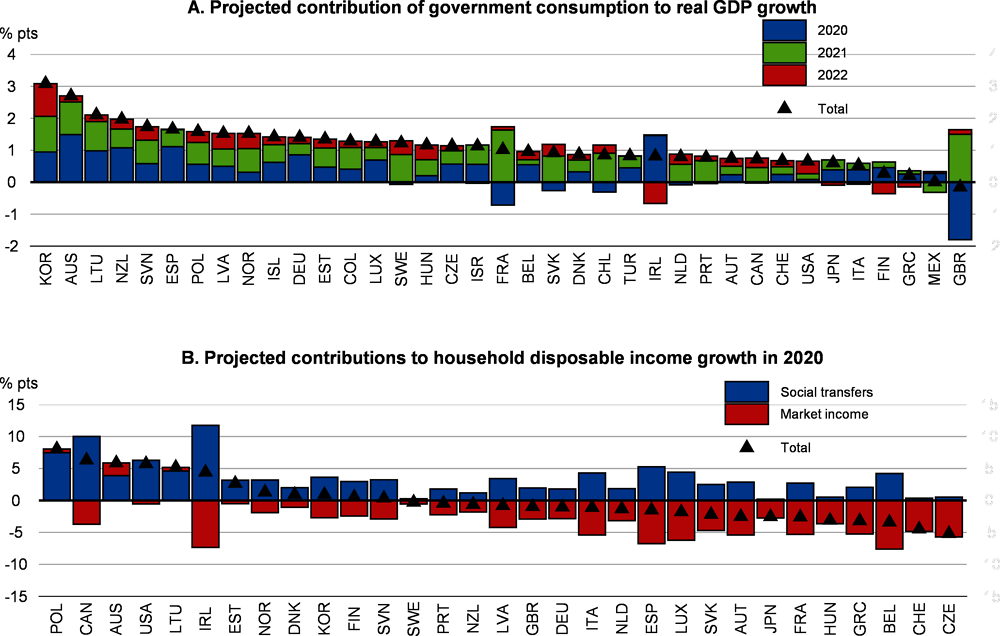

Public consumption is estimated to add on average around 0.4 percentage point to real GDP growth in 2020, and more than 1 percentage point in a few countries (Figure 1.20, Panel A). The average contribution is more than twice as large as during the global financial crisis.14

Social transfers are estimated to have helped offset some of the decline in household market income, resulting in a much smaller decline in disposable income or even an increase in a few cases (Figure 1.20, Panel B).15 The average support for household disposable income from social transfers in 2020 is about 30% larger than in 2009 once differences in the market income loss in these years are taken into account.

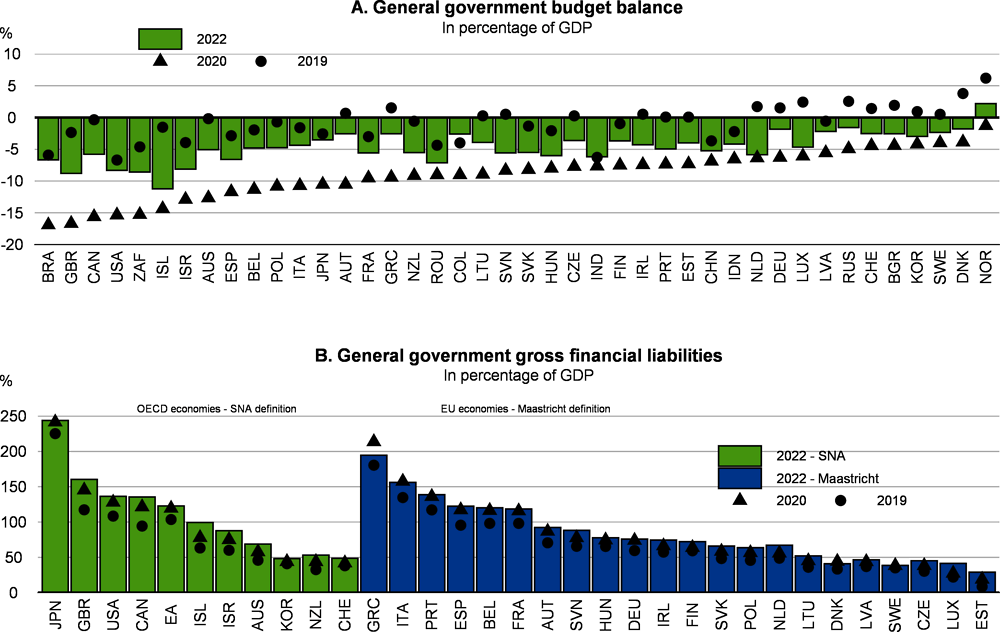

The working of automatic stabilisers and new support measures are set to result in large budget deficits in 2020, around 8¼ per cent of GDP on average across OECD countries and over 15% of GDP in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 1.21, Panel A).

Strong and timely fiscal support was necessary given the unprecedented scale of the negative shock and a high degree of uncertainty. Without the decisive fiscal response, the loss of economic activity, income and employment, and the associated increase in income inequality, would have been larger in the short term and longer-lasting.

Fiscal support still needs to be maintained over the next few years but its size and nature should adapt to the changing situation. Given large fiscal needs, government support measures should be spent well and be cost effective. The initial broad support to the whole economy will need to evolve gradually towards more targeted support to the hardest-hit sectors, facilitating labour and capital reallocation from sectors facing a structural demand weakness (see below). Opting for a full and early expiry of special programmes in 2021 should be avoided, or offset with other more targeted measures. Consolidation could undermine growth excessively, and may not bring fiscal savings given that it could result in higher cyclical social spending and lower cyclical revenues. In the event of renewed economic weakness, the automatic stabilisers should be allowed to operate fully and current special support measures maintained or extended.

The current projections assume that some support measures will expire based on existing legislation (Annex 1.A). Thus, in many OECD countries, a discretionary fiscal tightening is projected in 2021-22, though not fully offsetting the earlier easing in most cases, as appropriate given the economic outlook. (Figure 1.19, Panels B-D). This, together with some cyclical improvement, should reduce budget deficits by 2022. In all OECD economies, budget balances will remain below 2019 levels, on average by around 4% of GDP, and in some countries will remain high by historical standards (Figure 1.21, Panel A). The projected large budget deficits and the fall in output level will lead to a sizeable increase in government debt-to-GDP ratios (Figure 1.21, Panel B). By the end of 2022, they will be nearly 20% of GDP higher than in 2019 in the median OECD economy, and over 40% of GDP higher in Canada and the United Kingdom. In many economies, government debt as a share of GDP will reach the highest level, at least, in the past four to five decades. Notwithstanding the increase in public debt in most economies, ensuring debt sustainability should be a priority only once the recovery is well advanced, due to persistently low interest rates, although planning for the steps that may be needed should start now.

Policy challenges in emerging-market economies and developing countries

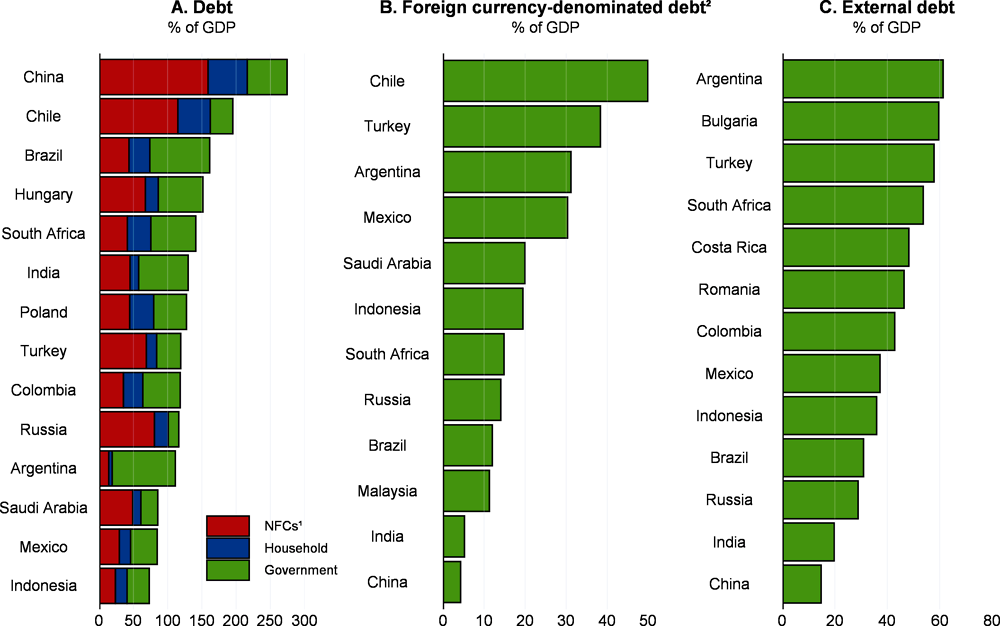

Many emerging-market economies entered the COVID-19 pandemic with a combination of high (private and public) debt, limited fiscal space and – at least for some countries – a significant exposure to debt denominated in foreign currency (OECD, 2020c; Figure 1.22).16 Exposure to foreign-currency-denominated debt has imposed an additional constraint on the monetary authorities in some countries, since monetary easing can amplify financial stability risks, via currency depreciations, and de-anchor inflation expectations. Foreign ownership of corporate bonds had also increased in some emerging-market economies and developing countries, potentially exposing them to rollover risks in the event that domestic currencies depreciate and revenues drop.

Governments in the major emerging-market economies, as well as some smaller economies, have been able to issue debt at relatively low rates over the past few months (IMF, 2020).17 A similar picture emerges for corporates, with firms in emerging-market economies – especially large and higher-rated firms – stepping up their bond issuance and increasing borrowing from banks to deal with the drop in revenues, refinance their debt, and/or build precautionary cash buffers. However, sovereign debt sustainability concerns are likely to re-emerge as the crisis lingers. These challenges are also likely to be aggravated by fragilities in the corporate and banking sectors.18

Many emerging-market economies eased their monetary policy stance and expanded fiscal support in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, which was facilitated by policy easing in advanced economies (Figure 1.18). This swift and strong policy response succeeded in preventing a sharper economic contraction, eased liquidity pressures on private agents and relieved stress in key segments of the funding market. Discretionary fiscal support also cushioned the impact of the shock on household jobs and incomes, especially at the lower end of the distribution.19 The latter development has been particularly welcome in emerging-market economies, as – in many of them – remittances collapsed and automatic stabilisers are generally weaker because of high levels of informality.

Whenever possible, emerging-market economies should continue policy support to avoid unnecessary long-term damage to the economy. The duration and strength of any additional policy response, however, will have to be tailored to domestic and external conditions.20 More importantly, as the crisis lingers and additional policy support becomes costlier, policymakers might need to move away from full-fledged support and prioritise more targeted policies.